Types of camel.

It was Aristotle, in his work The History of Animals, who noted that there were two types of camels. The Bactrian, who had two humps, and the dromedary who was afforded a single hump[1]. Though he may not have been the first to make this classification (as I will come to) he did allot the two-humped species the name ‘Bactrian’.

Bactria was a region the Greek identified which covers parts of modern day Afghanistan. Though Aristotle was correct in giving an eastern origin to the Bactrian camel he wasn’t aware that it’s homelands had once been much further to the east. This contrasts with the dromedary who inhabited north Africa and the Arabian peninsula.

Both animals had a profound effect on humans through antiquity, they served as mounts and not only nourished trade routes but also the odd belly. Humans had hunted and interacted with camels as they did many animals, particularly the dromedary. However, it was around the turn of the 1st millenium BC where their real value came to the fore and this was done through their domestication.

The early relationship.

Proving when an animal was domesticated is a difficult thing, it’s not enough to prove that humans knew of the animal in question, but that they were using it. Bones in or near a settlement might be the result of a successful hunt, likewise an image or depiction may simply be an acknowledgement. It’s only when the evidence starts to accumulate in context and in different types that an argument concerning domestication can be made.

For the dromedary the domestication seems to have occurred around the turn of the 1st millenium BC. At sites such as Uruk, Ur and Nippur dromedary figurines were discovered. Some had harnesses or saddles marked on them – a clear indication that they were being used as mounts. At the site of Tell Sheikh Hamad in eastern Syria the bones of a dromedary were found amongst other domesticated animals[2]. In theory this could have simple meant that dromedaries were caught and butchered there, except any hunter would do well to capture a dromedary in that part of the world as the dromedary doesn’t naturally dwell there.

The site was on a valuable trade route and the non-too-difficult premise is that dromedaries were being used as pack animals to move goods along these routes. It might be an obvious utilisation of the camel but at its inception it was a ground-breaking idea. Two archaeologists, Lidar Sapir-Hen and Erez Ben-Yosef researched this in a study on copper production sites and trade centres in the Aravah Valley[3]. Focusing on Timnah (southern Israel) and Wadi Faynan (Jordan) they concluded that around 930 BC there was a substantial reorganisation of how copper was smelted and and transported. Key amongst these was the use of the dromedary as a way of facilitating trade.

For the Bactrian camel the domestication date may well be earlier. This is largely because the Bactrian was being used further to the east and in a trading capacity. In fact one argument even suggests that it was the introduction of the Bactrian camel to the Arabian peninsula which moved the dromedary off the menu and into the workplace[4].

An early reference to a Bactrian is on what’s known as the Broken Obelisk which listed detailed of the Assyrian King Assur-Bel-Kala (1074-1056 BC). Here the reference is for a camel, most likely Bactrian, as being resourced from the east. One criticism is that the context might not be trade and instead the king amassing unusual animals.

We meet a different problem when dealing with epigraphic evidence. The term ‘Bactrian’ and ‘dromedary’ were made by Aristotle much later, these separate words had yet to exist. How then to decide what camel is being referred to? In the instance of the Broken Obelisk common sense (that the Bactrian was the only species of camel to the east) might be employed, but it’s argued that there were also specific words for the types of camel at this time.

The UURA=hubullu lists were a sort of Babylonian encyclopaedia. Domesticated animals were included and three words existed which meant camel. It’s argued that two referred to the Bactrian, leaving one for the dromedary. Interestingly this translated as ‘the donkey of the sea’. Not the most elegant description but yet another association with it’s prime function, carrying goods.

The camel in action.

As we move into the 9th and 8th centuries BC the evidence for domesticated camels increases. The Assyrian King Shalmaneser (858-824 BC) recorded a number of victories on a stele known as the Black Obelisk, this included references to camels in the inscription. Also depicted were Bactrian camels being led as tribute.

Bactrians depicted on the Black Obelisk.

The tendency to record victories on stelae in this time and just after by rulers in Mesopotamia is incredibly useful for so many things, camels being just one of them. Tiglath Pileser (744-727 BC), Sennacherib (704-681 BC and Esarhaddon (680-669 BC) all featured camels as tribute or a prize of war. Yet there was also visual evidence that camels might be used in war, not just relegated to the spoils of it.

An Assyrian relief dating to 728 BC shows an individual fleeing on a dromedary from horsemen. It’s possible to consider this image as representing a by product of warfare. Perhaps the rider is a civilian, though a relief dating a century later leaves no such grey area. The image comes from the north wall at the palace of Ashurbanipal and dates to 650-600 BC. Assyrian soldiers chase what has been identified as an Arab contingent who are acting as mounted archers, but atop a dromedary. The dromedary was sourced in the Arab peninsula and its abilities in desert fighting must have set it apart from the horse. There may also have been another unintended benefit the camel had which was to turn the tide of history.

Mounted archers using dromedaries from Ashurbanipal’s palace relief.

In 547 BC the Persian King Cyrus faced the Lydian King Croesus in the battle of Thymbra. For Cyrus the need to expand westwards into western Turkey had been checked by Croesus. Cyrus understood that his opponent possessed enviable cavalry and took the camels from his baggage train. He equipped these as cavalry and sent them against the horse cavalry which was scared by their smell. The cavalry was in disorder and Cyrus was able to rout the wings, winning the battle. With Croesus beaten Cyrus had western Turkey and the Aegean open to him. It might seem a small consequence, but the creep of the Persian empire now found its way to the Ionian coast and the Greeks. Decades later this would lead to the famous conflict between Greece and Persia. All this perhaps helped by the scent of a camel.

The Classical Camel.

The movement of the Persian empire didn’t announce the camel to Greece. Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, deigned to describe the camel as he felt everyone would know what one looked like[5]. Though it would have been nice to know whether he meant dromedary, or Bactrian (or both) it is a insight into how familiar Greeks were with them. Herodotus wrote his Histories for Greeks across a range of modern countries and locations. As such, Greeks in colonies in Southern Italy and Sicily must have been assumed to know what one was.

Herodotus associated the camel with speed and and as a baggage animal. In the case of the former, we have a story often mocked for its fantastic nature but the tale probably has some bearing on real life events. In book 3 Herodotus discussed fox-sized ants in faraway India. These ants would dig underground and their burrowing would bring gold-rich earth to the surface as they excavated their burrows. Knowing this the locals would arrive and seek to make away with it in sacks. To ensure a safe getaway they used camels.

French ethnologist Michel Peissel discovered that in the Deosai Plateau (northwest Pakistan) locals use the spoils from marmot burrows as a source of gold dust, so the action Herodotus describes may be based in reality. However, this doesn’t explain the involvement of ants until, as Peissel pointed out that marmot and mountain-ant are similar words in Persian. As such it may have been a simple translation issue.

Herodotus didn’t just mention camels as getaway options. The poor beasts were predated upon by lions when the Persian King Xerxes marched his army into Greece. Here they were acting as they often did for armies, as an able baggage train. Herodotus queries why the lions specifically went for the camel and not the other pack animals, which is an interesting question. But I wonder if there wasn’t a metaphor being used here; the eastern animal being savaged by one which was then native to Greece.

A definitive association between ‘eastern’ and ‘camel’ is made as a joke by the comic playwright Aristophanes. When a Persian bird arrives in his play ‘The Birds’ one of the characters quips as to how it got here without a camel[6]. Aristophanes also noted what Cyrus had well understood, that camels are quite pungent. When describing a terrible creature in The Wasps he affords it “the arse of a camel”[7].

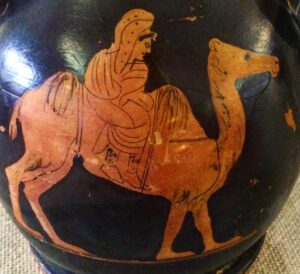

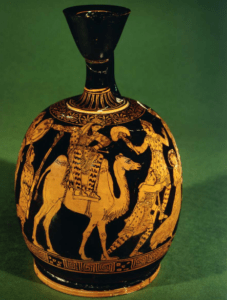

In art two vase images survive, both from the 5th century BC and both featuring camels. The more elaborate and detailed vase image has a Bactrian ridden by a character in full possession of the regalia of an easterner, even down to the patterned trouser. The other image is less detailed, and but also seems to have a Bactrian. The second hump is less pronounced but matches the larger one in terms of detail, specifically the hair on it.

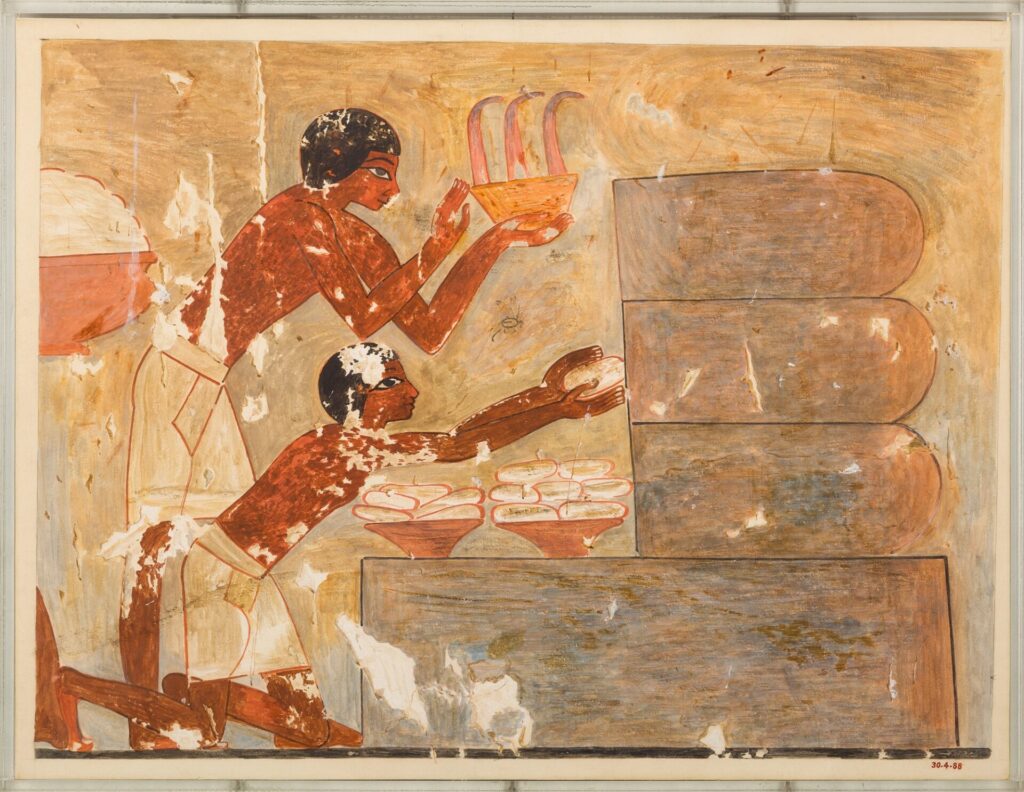

One mediating culture between the east and Greece was Egypt. But here the camel was less utilised. The Egyptian’s borrowed the Semitic word for camel, not even allotting it their own. This is surprising given that its lands bordered and could easily access both Bactrian and dromedary. Why the decision not to make use of the camel?

One argument is that the Egyptians marked it down as an unclean animal and therefore not worth investing in[8]. It could also have been that as Egypt utilised the Nile for trade and travel perhaps there wasn’t the need for an animal with such abilities. That said, there must have been a substantial rationale behind it. Dromedaries only come into Egypt in the context of trade in the later 1st millenium BC (and made standard there by the time Rome took hold of it).

Rome.

Rome had an empire to govern and the camel (both the Bactrian and the dromedary) were perfect to sustain its various trading routes. One her blog Dr Caitlin Green wrote a piece based on a study which discussed the remains of camels all across Europe in the Imperial Period of Rome (1st to 5th centuries CE). Camels even travelled as far as London. That’s not to say that the camel, specifically the dromedary, was absent from military service. As has been seen, the dromedary was far more useful in desert conditions than the horse. A dromedary cavalry unit was stationed in Syria under Trajan. The ala I Ulpia Dromedariorum milliaria numbered approximately 1,000 dromedaries and was most likely used to scout and patrol as opposed to direct engagement.

The camel was still identified as eastern and appeared on coins Trajan issued in Arabia. All coins were important propaganda, perhaps the Bactrian’s inclusion aimed to wed the mercantile association of the Bactrian with Trajan? A reminder that prosperity was ensured through his reign.

Throughout its relationship with humans the camel, both Bactrian and dromedary, was vital in the development of trade and therefore linking cultures together. Without it we might wonder how much the growth of those early trade routes would have been. It is certainly an underrated animal.

Bibliography and further reading.

Aristophanes, The Birds, The Wasps.

Aristotle, History of Animals.

Bartosiewicz, L. Camels in Antiquity: Roman period finds from Slovenia. Antiquity, June 2015.

Gaudard, F. The Camel as a Sethian creature. Essays for the Library of Sheshat. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, No 70.

Herodotus, Histories.

Magee, P. When was the dromedary domesticated in the ancient Near East?

Orlando, L. Back to the roots and routes of dromedary domestication. PNAS June 14, 2016.

Potts, D. Camel hybridization and the role of camelus Bactrianus in the ancient Near East.

Sapir Hen, L and Ben-Yosef, E. The Introduction of Domestic Camels to the Southern Levant:

Evidence from the Aravah Valley. Tel-Aviv, November 2013.

Tomczyk W. Camels on the Northeastern Frontier of the Roman Empire. Papers from the institute of archaeology, 26.

[1] Aristotle, History of Animals. Bk 2.

[2] Magee, 269.

[3] See reading list.

[4] Magee, 273

[5] Histories, 3.103

[6] The Birds, 277.

[7] The Wasps, 1035.

[8] See Guadard for this and the argument of associations with Set.