Trebia – extra bits.

Trebia was a huge gamble which ultimately paid off, here’s some extra content which I hope helps.

Maps/images.

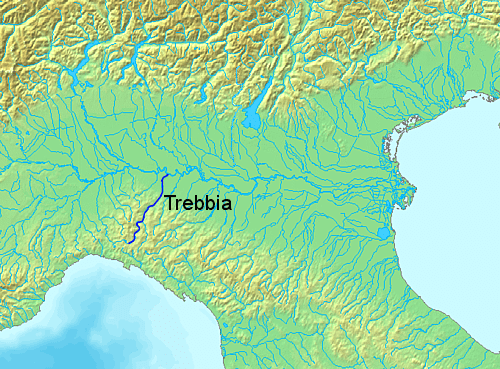

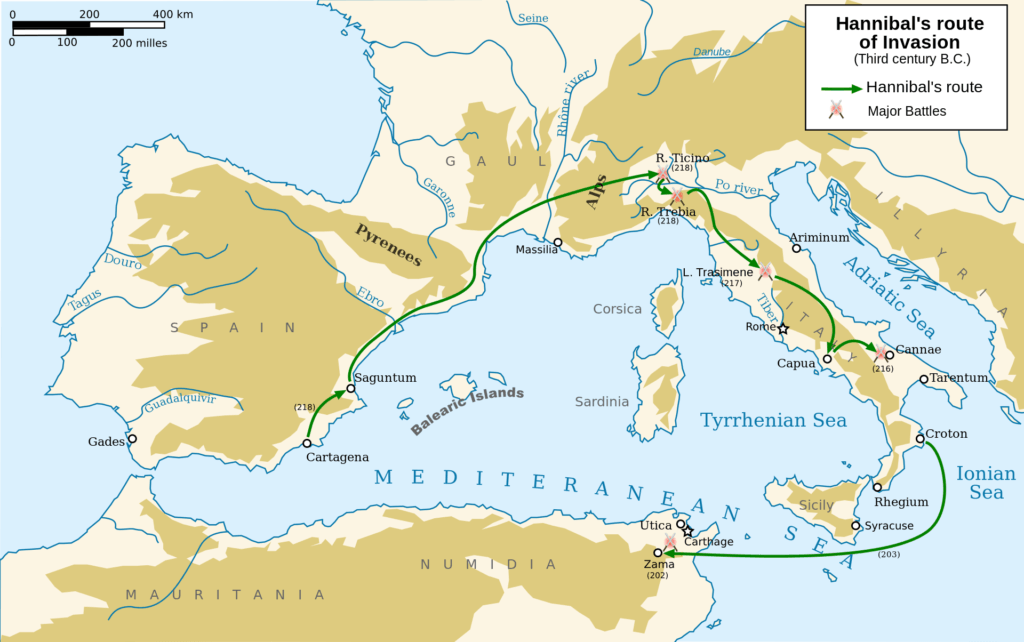

Ever wonder what that route was?

Here’s Northern Italy with some of the place names mentioned (and the course of the Po river).

Trebia

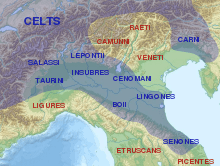

Some of the tribes in northern Italy.

The falcata (curved blade)

The Trebia river (modern day Trebbia), not the section forded.

The Roman troop types I mention.

Top the hastati, bottom left principes and bottom right the triarii.

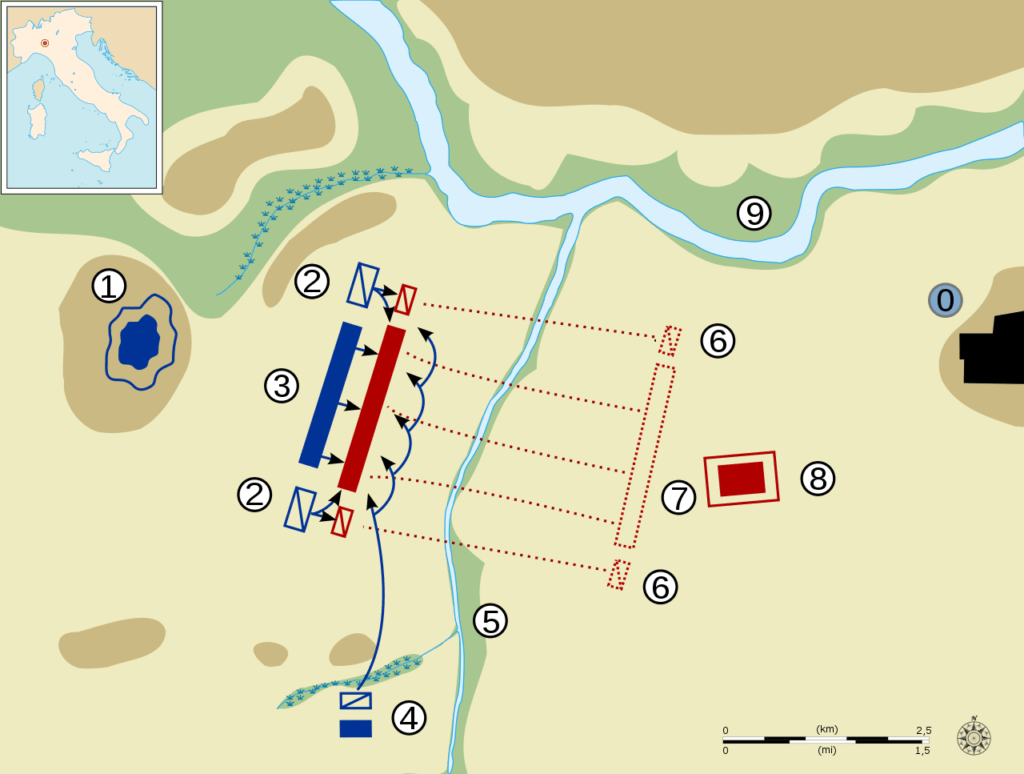

The Battle.

Hopefully I have explained this clearly on the episode, but it can help to visualise it as well. The Roman army is red and you can see that as it moved across the Trebia and engaged the hidden units with Mago were able to fall on the rear.

- Hannibal’s camp.

- Hannibal’s cavalry and light troops.

- Hannibal’s infantry.

- Mago.

- The Trebia.

- Roman cavalry.

- Roman infantry.

- Roman camp.

- The Po river.

Slingers.

Ever wonder what they could do? Here’s a nice video and at 5.13 you get to watch modern day Balearic slingers.

Further Reading/Sources used.

Livy, The History of Rome.

Polybius, The Rise of the Roman Empire.

Lancel, Hannibal.

Lancel, Carthage.

Goldsworthy, The Fall of Carthage

Cunliffe, The Ancient Celts.

Episode Transcription.

The Battle of the Trebia was Hannibal’s first major engagement with Rome. But how had this come about? Who were the major figures that day and how did the events of the battle unfold? Join me as I discuss all this and much more on the Ancient History Hound podcast.

Hi and welcome to the Ancient History Hound podcast, my name’s Neil and as you might already know you can find me on twitter as @ancientblogger and this podcast now has its own handle @houndancient. Feel free to come and say hi.

I don’t just tweet, I have a website – ancientblogger.com and here you can find links to my instagram, Youtube as well as more ancient history content including the notes for this episode. Recently I’ve shamelessly joined TikTok as ancientblogger – but have no fears. Much like my YouTube and instagram it’s all ancient history content. Not a dance move in sight.

Now, what really helps is if you can rate or review on the platform you listen to and this now includes Spotify.

With all that said and done what can you expect from this episode? To help give the Battle of Trebia some context I will be exploring the events which led up to it as well as other aspects. For example, the characters involved and how Hannibal exploited both the political and geographical landscape to his advantage. And of course the battle itself. I hope this will give a more informed and hopefully interesting experience.

Two final things just so you know – the events occurred in the 3rd century BCE, so take it as read that any date is BCE or BC unless I mention otherwise. Call me lazy but it feels nice not having to say BCE all the time. For the purposes of practicality and not laziness, honest, I’ve used the word ‘celt’ a few times, where applicable I do mention specific tribes but take this term as a catchall for a range of separate tribes who are often grouped together under this word.

Ok, I think that’s everything so I’ll begin

In the Spring of 218, either April or May, a Carthaginian General called Hannibal left camp and began a march which would result in him fighting deep in the Italian Peninsula. He couldn’t have known that in the space of a few years he’d bring about defeats on Rome which became near legendary. This included the Battle of Cannae which is still studied today in the context of military perfection. He’d make a huge impression both on Rome and the history books, the phrase “Hannibal at the Gates” became a term used by Romans to invoke the scariest of propositions.

Hannibal was Carthaginian, he was from North Africa, yet the first step made on the march wasn’t trod on African soil. Instead it was Spanish. This might be surprising but by 218 Carthage had established a base of operations, almost a mini Kingdom in the south east of the Iberian peninsula. The reasons for this are complex and actually form the content of an episode I recorded a few years ago called Costa Del Carthage, so I won’t go into too much detail but I do think it’s worth providing some form of an overview because much of what happens now is linked to what happened during and after the First Punic War.

Between 264 and 241 Rome and Carthage fought each other to near exhaustion in a series of battles, more often naval ones, in and around Sicily. This island was prize worth fighting over, strategically just look at a map and see how important it was for a growing Roman state. But there were resources there and it was a fabulous trading hub. Prior to the war Sicily had largely contested by the Greeks and Carthaginians before Rome joined in – and Rome were ultimately the victors.

The treaty of Lutatius followed, this was negotiated by Hamilcar Barca – a general who had been a continual thorn in the Roman side on Sicily. As Rome had won the treaty was on their terms and two outcomes are notable for the context of this episode – that Carthage had to exit Sicily and they were to pay Rome a hefty war indemnity.

Hamilcar returned to Carthage and faced a political landscape full of enemies, even though he had put down a rebellion of unpaid mercenaries and helped save Carthage from them.

What Carthage needed was a way to replenish its finances and build up its prestige and there was one place to do this, the southern Iberian Peninsula, or modern day Southern Spain. Carthage was originally a Phoenician colony and the Phoenicians, hailing from modern day Lebanon, had set up various trading posts and colonies across the Mediterranean. One such example is modern day Cadiz.

Through this network Carthage knew that southern Spain was very wealthy in terms of what could be mined there, in particular silver. With the trading posts they had a knowledge of the tribes and a lot of the information which made the next move a sound choice. We don’t know the exact motivations for why in 237 Hamilcar headed to Cadiz with a small force, but the chance to restore their fortunes and restore Carthage as a power seem the most logical.

Accompanying Hamilcar to Spain was his 9 year old son, Hannibal.

Roll forward a few years and what had resulted was a Carthaginian base, Carthago Nova or modern day Cartegena. Hamilcar had been every bit as successful as he could have hoped in both winning over the local Iberian tribes or simply beating them. After he died his son-in-law Hasdrubal took over and when he died it was Hannibal’s turn. By this point Hannibal had accumulated the sort of experience which was to make a lot of what he achieved possible.

War with Rome was seemingly something Hannibal inherited from his father and in 218 this was formalised by a famous Roman embassy sent to Carthage following Hannibal’s siege of Saguntum, a settlement on the east coast of Iberia. Fabius Maximus stated to the Carthaginian Senate that he had war or peace in the folds of his toga, and it was up to them to choose. The result was war.

Hannibal’s objective wasn’t to defend against an imminent Roman attack, or fight them in a disputed area. His military experience had been of conquest and expansion in the heartland of the enemy and a question sometimes asked is why didn’t he sail his army across the Mediterranean sea? Surely it would be easier?

In some ways it would be. But only if you could magic up a huge fleet of ships, guarantee that the weather would hold throughout the trip – remember that ships ladened with supplies sit low in the water and the smallest of storms could cause mayhem. You’d also need to avoid the Roman navies which would find these ships ladened with supplies and soldiers easy pickings. And presumably keep the massive ship building you were doing or that magicked up fleet secret from Rome.

Finally when you got to Italy you’d need to ensure that Rome gave you enough time and space to disembark and set up a camp. In short, it wasn’t ever an option and that’s why Hannibal marched his men all that way.

The exact route isn’t known, the most famous part of this was crossing the Alps and this too remains a hotly debated topic. But we know that Hannibal marched north, crossed the Pyrenees and moved across the south of modern day France. He then crossed the Rhone valley before that famous crossing over the Alps before descending into the Po Valley, probably near Turin.

This was approximately 1,000 miles or 1,600 km and I know that I have listeners across the world so I thought I would see what that might be in terms of marching between cities outside of Europe. Give or take a few steps it’s around the same as walking from New York to Tampa bay in the USA or from Las Vegas to Dallas. Travelling south from Cairo it would get you to Khartoum in Sudan and for our friends down under think of travelling from Adelaide to Brisbane.

Now the subject of numbers allows me into a segue of sorts into the speculation over the size of the force which started the march. Polybius, a Greek historian and one of our two main surviving sources for Hannibal’s campaign wrote that the infantry was 90 thousand strong with 16 thousand cavalry. After crossing the Pyrenees this was reduced to 50 thousand infantry and 9 thousand Cavalry.

The force which crossed the Rhone Valley was smaller still at 38 thousand infantry and 8 thousand cavalry and the final force which descended the Alps in October or November 218 was 20 thousand infantry and 6 thousand cavalry. The reduction in numbers has been explained through desertion and death, after all there was fighting on the march with tribes, particularly in the Alps. But there would have also been attrition from people either dying naturally or deserting and on that Hannibal himself apparently sent home 10 thousand Iberians because he suspected they would rebel. There’s also a suggestion that some were stationed along the route in order to secure it as a supply line, though I should add that this is contested.

Crossing the Alps cost Hannibal dear, according to Polybius he descended the southern slopes with an army of 20 thousand infantry, consisting of 12 thousand African troops and 8 thousand Iberians and 6 thousand cavalry. This number is less speculative than the previous ones as Polybius wrote that this was recorded on a column at Lacinium.

The march itself was full of encounters and a few near near ones with Rome. I realise in all of this I haven’t mentioned them much. They were aware of what was happening and the Consul Publius Cornelius Scipio had led a force which had tracked Hannibal in in and around the Rhone Valley. In one instance he led a force which defeated the Carthaginian cavalry and came close to catching Hannibal who wasn’t interested in fighting, he needed to get across the Alps as soon as possible and into territory which might give him some reprieve.

And that’s because northern Italy or Cisalpine Gaul as it came to be known wasn’t Roman. It was instead the home of a number of Celtic tribes such as the Boii and Insubres. These tribes were age old enemies of Rome, in 390 they had famously sacked it. More recently, in 225, a confederation of Celtic tribes had risen and moved south through modern day Tuscany and fought Rome at Telamon. The result was a defeat for the Celts and in response Rome had been inching northwards. Colonies at Placentia, modern day Piacenza and Cremona resulted and these became areas contested between Rome and the Celtic Tribes.

All of these events weren’t unknown to Hannibal, in fact prior to setting out on his march he’d been in contact with the tribes. He’d sent embassies and gifts in an attempt to forge an alliance. This had been successful, I’d expect that the Celts knew about Hannibal and had heard of the rise of Carthage, albeit in Spain. If the saying “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” is true then Hannibal and the Celtic tribes were absolute besties. Of course there were concerns on the part of Hannibal. The Celts could be a great addition to his effort both in offering safe passage and as a recruitment option. But they would only respect success, if Hannibal looked to fail or wavered then his army would become a very attractive proposition for all the wrong reasons.

Luckily Hannibal had an early opportunity to demonstrate his abilities. After resting his men and gathering supplies he moved to the nearby base of the Taurini, probably modern day Turin. The Taurini hadn’t been friendly and were enemies of the Insubres, as you may have guessed the Celts were often at war with each other. After a three day siege Hannibal took the capital and slaughtered anyone standing and this had the intended effect of proving himself to the wider Celtic community.

And here’s a good place to pause and listen to a podcast you might be interested in.

(Khameleon promo)

As ever – if you want to swap promos or just have your ancient history podcast featured let me know and yes, it’s free.

Hannibal how had a force operating in northern Italy, one which had been honed by continual marches and fighting. I’ve so far spoken about numbers and broader categories of units, such as infantry. But what was his army composed of, what would Rome be facing?

I’ll start with the infantry which were predominantly split between the African and Iberian and with the African troops. When Hamilcar had first arrived in southern Spain all those years ago he’d have taken this troop type with him. Perhaps there were some soldiers in the current army who had belonged to that group. The majority would have been recruits sent over to southern Spain and who had fought there.

The soldiers were sword based infantry from what we can tell and would have had a shield with minimal armour. The Iberian troops were similar in many regards, I say Iberian but these came from different tribes. They were either mercenaries or supplied to Hannibal as part of a military tribute from those he had conquered there.

Iberia at this time was given to numerous tribes who were often at war with each other and as such these were ideal for Hannibal. A particularly nasty looking sword they used was called the falcata but they also brough with them a straighter blade. This so impressed the Romans that after the 2nd Punic War they adopted and then adapted it. What resulted was the gladius Hispaniensis, this translates as “the Spanish sword” or the gladius to you and me. It changed in size and shape over time but it was this weapon which would become the iconic sword of the Imperial Period.

Both the African and Iberian troops were high quality and by this point far more experienced than their Roman counterparts could hope to be.

Adding to this was the Celtic infantry, these started to join up with Hannibal and though they hadn’t been on the march with him they were still very useful. The Celtic tribes had a martial culture, much like the Iberians in that they advocated fighting as a cornestone of who they were. The basics for a Celtic warrior at this point would have been sword, possibly a spear and large shield.

The Celts also allow a segue into the cavalry, because they supplied strong heavy cavalry and by that I mean that they were capable of charging and getting stuck into the enemy either on the horse or dismounting. This differed somewhat from Hannibal’s other cavalry, possibly the most famous of his troops. The Numidian cavalry.

These fought differently and relied on the mobility and skill of the riders to get near to a unit and pepper it with javelins, and then move off. They could fight from horseback but their primary attribute was mobility. To get round and enemy and attack from behind and much of Hannibal’s strategy relied on manifesting this type of situation. I should add that there was also Iberian cavalry which was akin to the Celtic in that it would fight up close and very personal.

Giving further diversity both in terms of what they could do and where they came from were the Balearic slingers. These hailed from the Balearic Islands east of Spain, and you will have heard of one of these islands – Ibiza. I say hailed because skilled slingers could be devastating if used correctly. Slings might sound a bit old fashioned, even in this time but they were very dangerous. Balearic Slingers were renowned for their accuracy, they carried three slings each, presumably for different ranges and would use either lead bullets or stones. And these could cause a multitude of problems for anyone on the receiving end. They could kill if they struck you on the head, but even if they didn’t, perhaps you were wearing a metal helmet. There would be concussion. And if it hit elsewhere on the body you might suffer a broken bone.

Above all of this was the psychological aspect. The slingers could pin down a heavily armed unit and keep it occupied knowing that it wasn’t going to get near them. These were added to Hannibal’s light infantry whose main job was to keep the enemy bothered and harassed from a distance.

Finally, the elephant in the room, and I mean that. Hannibal had 37 elephants at Trebia, I recorded an episode on the War Elephant and in short they were often more dangerous to the side using them as they were fighting. The irony is that Hannibal is strongly associated with the elephant but they didn’t have much of an input in any battle he fought with Rome.

This force was one which Hannibal needed to bring against Rome in some form or another and he was matched in this attitude by the Roman Consul Scipio. He’d brough an army north and was looking to catch the Carthaginian force which had evaded him near the Rhone. After hearing of his achievements against the Taurini Scipio took his men and marched along the Po river before building a pontoon bridge to cross the Ticinus river, a tributary of the Po.

It was near the Ticinus that Hannibal and Scipio crossed paths and almost literally. Both were aware that the other was near but neither knew how close until intelligence came through to them respectively that the other was close. Setting up camp the two assembled a force composed mainly of cavalry to find out exactly where the other was, and they ran more or less headlong into each other. This became known as the Battle of the Ticinus, something of an exaggeration as was really a clash between the two scouting parties. Hannibal was able to pin Scipio’s smaller force and then the Numidian’s got round and attacked from the rear.

Scipio only just made it out after receiving a nasty leg injury and according to the anecdote it was his son, Scipio, who was to later take the war to Carthage in Spain and face Hannibal at Zama, who saved his father.

Scipio was quick to break camp and retreat across the Ticinus, breaking up the small bridge he’d made to ensure the pursuing Carthaginian army couldn’t follow. This might sound an overreaction but the landscape where he’d camped was wide and flat, perfect for Hannibal’s cavalry which he now understood the importance of.

Things were to get worse for Scipio. His next camp was made nearer Placentia where he intended to reset and work out his next move. But disaster struck and this time it was the Celts. Even though Rome had fought against the Celtic tribes there were some tribes allied to Rome and who fought on the side of Rome. A number of these decided to defect to Hannibal, after waiting till the middle of the night they slaughtered the sentries and many of their Roman colleagues, cutting off their heads they disappeared into the November night and headed to Hannibal.

Scipio realised that the situation had worsened and also that the Celts were likely to cause further problems. Breaking camp once more he moved south crossing the Trebia and picked a hilly spot to camp, this would at least prevent Hannibal’s cavalry. But as we’ll see the defensive position was never going to be a factor.

As much as Scipio was suffering Hannibal’s fortune and stock was rising. He took Clastidium, modern day Casteggio which was primarily a grain depot. And it wasn’t just the supplies which were coming thick and fast. The Boii, a large Celtic tribe brought Roman prisoners to Hannibal and declared a formal alliance.

Scipio was joined at his camp by his fellow Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus who had been posted to Sicily with his army. The expectation would be that both Consuls would decide the military strategy from this point on, but with Scipio side-lined with an injury the events would be largely led by Longus. And Longus is given to us as a very different character to that of Scipio.

He was feisty and impetuous. We might picture the pair of consuls as a squabbling couple perhaps suited more to an 80s sitcom trope than leading Rome’s armies. Scipio had seen up close what Hannibal was capable of and so seems to have respected him and advocated for a much more cautious policy.

This is certainly how Polybius paints the pair, but there may be a bit of propaganda behind all of this. A point Goldsworthy makes is that Polybius, who largely sets the scene between the two, was a good friend of Scipio Aemilianus, a later relative of Scipio. It wouldn’t be unreasonable to think that Polybius fashioned an image of Scipio with hindsight duly applied.

Longus, after all, was acting within the social and political expectations of the time. Firstly, he was Roman and Rome beat Carthaginians. Secondly, he was a consul. For any consul the opportunity to beat a Carthaginian force which had allied with Celts and had put one consul out of action, well, it was as good as it could ever get. This was a dream ticket and Longus must have been thinking of everlasting glory, he just had to kick this pup upstart back over the Alps.

The thing worth knowing about Consuls and the political system which they were a part of was that this temporary role, for 12 months, was when you could amass fame and fortune. Becoming a consul usually meant you had spent large amounts of money, often borrowed, called in a lot of favours and put several noses out of joint. It was important then to try and ensure everyone got what they want because after the 12 months you could be held accountable for your actions. It’s an odd analogy but I think of it as akin to a timed supermarket trolley dash. This was your chance to pay anything back, kiss all those disjointed noses better and try to make yourself as politically safe as possible for when your term ended.

The political setup of Rome encouraged short term success gathering, wherever it could be found. Longus and Scipio were both deep into the terms of their consulships. Soon they’d need to return to Rome to oversee the elections for the next consul who would take charge in mid-March. So when Scipio apparently advised Longus to caution, to keep the men in camp and train them you can understand why Longus felt these were the words of a jealous colleague who didn’t want the glory to fall to him.

Events were to conspire which would further convince Longus of his policy to engage Hannibal as soon as possible. In response to a Carthaginian raiding party Longus set out a force to intercept it which it duly did. Events, as they say, escalated and it seemed for a moment that this might become the definitive battle. However, Hannibal pulled his men back in a retreat.

Longus understood this as you might expect, not a skirmish to understand and rationalise how he had won, but a full blown victory against Hannibal. It vindicated his view that this was his moment in time. For Hannibal the clock was also ticking, much of his campaign was built on momentum, particularly with the expectation of his Celtic allies on his shoulders. He needed a battle and had a general in the form of Longus as easy as any to bait. He just needed to pick where the victory would be.

And here I think it’s worth giving an overview of the force Hannibal would be fighting.

In short Rome’s army at this point was not the professional Empire building outfit you might be familiar with. These were largely farmers and other citizens who fought when charged to do so and whilst they were certainly capable I wanted to draw that distinction between this period and the later profession armies. Broadly speaking the soldiers fell into three types of infantry, the hastati, principes and triarii.

Both the hastati and principes were sword based infantry. The difference between them being the armour worn and their respective ages. Hastati were the young men who fought in the front line, as mentioned, with a sword and shield. They had a helmet and at the most a metal plate covering their chest. Principes may have had mail, were older and fought in the second line, and I say may because this army supplied its own equipment. The triarii were a throwback to the spear based infantry Rome once fielded. They were veterans, albeit in age and not necessarily experience. These men fought in the third line, hence the Roman saying “going to the Triarii” which meant something like “going to the wire” or “down to the last man”.

Lastly and certainly least there was the cavalry, his was for those who could afford a horse. They weren’t on a horse by virtue of being excellent horsemen and this weakness in cavalry both numerically and in terms of quality was to be horribly realised.

Perhaps it’s easy to see why Scipio was so hesitant at putting these men into the field. It may have been a capable force in some regards, but Hannibal certainly had a better quality of troops and more importantly a force which had been on campaign and fighting for several months.

Between the two camps ran the river Trebia, this time of year it was swollen with the ice and snow and it wasn’t just associated with the battle by virtue of its geography. As you’ll hear Hannibal began to draw on the elements and geography of the area to their maximum effect against Rome.

After scouting the area Hannibal noted a feature which was to prove decisive. A stream bed his side of the river ran tandem to the river and to the west of his camp. Any Roman force would first cross the river to and then move past this. It was a perfect spot to hide troops who would then fall on the Roman rear once it was engaged with his main army. Under the command of his brother Mago 1,000 cavalry and 1,000 infantry were posted here the night before the battle.

Daybreak on the 21st December, the date traditionally given for the battle is around 8am and it was at this time which Hannibal reportedly sent his Numidian cavalry over to the Roman camp. A short assault did its job and roused Longus to action, he assembled the army and they marched out to meet Hannibal. Though Longus had supreme confidence in his men and his ability he hadn’t checked the details. His men hadn’t had time to have breakfast and were marching through the freezing sleet, in stark contrast Hannibal had ensured his men had eaten and were warming themselves. And this detail would doubtless have consequences the march, the fording of the river and assembling the Roman army in formation on the wide plain in front of Hannibal’s camp took several hours. Men were doing this cold and on empty stomachs.

They were also suffering from that river crossing. Polybius mentioned how this affected the men, the cold water exacerbating the near freezing conditions. Livy went further to describe the condition of the men as they followed the Numidian cavalry back to Hannibal.

“There was not a spark of warmth in their bodies and the nearer they approached the chilling breath of the water the more bitterly cold it became. But worse was to come – for when in pursuit of the Numidians they actually entered the river – it had rained in the night and the water was up to their breasts – the cold so numbed them that after struggling across they could hardly hold their weapons. In fact, they were exhausted and as the day wore on hunger was added to fatigue.”

It was in such a condition that the Romans formed up on the plain having crossed the Trebia. The infantry numbered 36 thousand. 16 thousand of which was Roman and 20 thousand allied. The allies were placed either side of their Roman colleagues and the 4 thousand cavalry were split and placed on the wings. Some 40,00 men made up the Roman army that day and Goldsworthy estimates that the front line of the infantry measured 2 miles.

Hannibal deployed his army in one single line. His infantry consisted of 20 thousand men with around 8 thousand Celts in the centre and the African and Iberian infantry either side. On the flanks were the elephants and 5 thousand cavalry on either wing. With the 8 thousand light infantry including the Balearic slingers the numbers of the two armies were similar but the composition was vastly different.

The opening moves were made by the light infantry, for Rome this was probably drawn from the allied troops whereas Hannibal had his the units I’ve specifically mentioned. The effects of the weather and the crossing became apparent at this point and Livy wrote how javelins had been impaired by the water and the state of the light infantry can only have been sub-standard.

When the Roman infantry charged Hannibal’s light infantry withdrew to the flanks and so began the battle of the Trebia. Hannibal’s advantage was with his cavalry in both numbers and quality and it was on the flanks that Hannibal focused his efforts. The centre was unlikely to ever compete with Rome which even now had the simple tactic of becoming a meatgrinder which looked to chew slowly through the enemy line. Hannibal had no expectation that he could match Rome here, even with the quality of troops. But he didn’t need to match the Roman infantry, he just needed to hold it.

Hannibal’s cavalry and light infantry on the flanks were quick to force the Roman cavalry back and send it galloping away. The flanks of the Roman army were now horribly exposed. The Balaerics used javelins and their slings, the cavalry either engaged proper or darted in and out with their javelins. The allied forces which were being hit now had to stop pushing forward as much and turn outwards to meet the peril there. Things must have looked bad for Rome.

And then Mago appeared at the rear of the Roman army.

Polybius wrote that the response to this was that it threw the army into confusion and dissaray. Any army would have issue with such a development, perhaps a more experienced and well drilled one might be able to counter in some way. Not because of weapon proficiency but in the context of an experienced army being familiar with how a battle might sway in terms of momentum. I’ve mentioned experience a few times, and in this context it’s important to understand it. Experienced soldiers could hold a line and understood that by not breaking they were always going to increase their chances of survival.

But not this army, not one which was less experienced and was hungry and half frozen. Mago’s force was the lid on the box, or more accurately the final nail in the coffin. The Roman force now fragmented into a blizzard of men running for their lives. Some made it to the river and past the cavalry but then many drowned trying to cross. The weather, which had done so much for Hannibal now prevented his men from chasing down what was left.

Testament to Rome’s bulldozer tactics was a unit of 10 thousand men who had broken through, realising what was going on behind them they marched to Placentia and safety.

Casualties are very difficult to estimate, particularly in a time when more died from wounds suffered days later than on the day of the fighting. Polybius subtracts the 10 thousand who made it through to Placentia and commented that a majority of the remainder died that day. If we take the lowest figure this could be it’s around 15 thousand men. Hannibal also suffered, but mainly animals, particularly the elephants. The casualtis mainly came from the Celtic forced assigned to the centre. Perhaps this was why they were placed there, it signalled to his Celtic allies that he had faith in them and diplomatically scored points. But on a practical level it also made sense. Hannibal knew the Roman tactic of pushing through the centre, so placing the troops he could more easily replace there, rather than the Iberians and African contingent, was a sound decision.

Hannibal was left to recoup and rest his men, the weather having taken its toll even with all the precautions he had taken. Longus survived and tried to spin a tale back at Rome that the battle was interrupted by a storm and as such the outcome wasn’t clear. But as stragglers returned the truth came out and Rome began to sense that they were in a state of near emergency.

Fortunately they had the rest of the winter to recruit and kit out a new army to send out with the upcoming Consuls. However, history was to repeat itself in a number of ways. By the summer of 217 Hannibal had undertaken a demanding march, he’d fought a Roman army and another body of water was clotted with Roman dead. This was the Battle of Lake Trasimene and it’ll be up next so subscribe if you haven’t already.

And if you’ve enjoyed this episode then feel free to come find me and say hi, or share or review or do whatever you do when you like what you listen to.

Until then take care, avoid freezing waterways and keep safe.