Gladiator scribblings.

This feels apt given the amount of graffiti and images of gladiators which we have. In any case here are some notes.

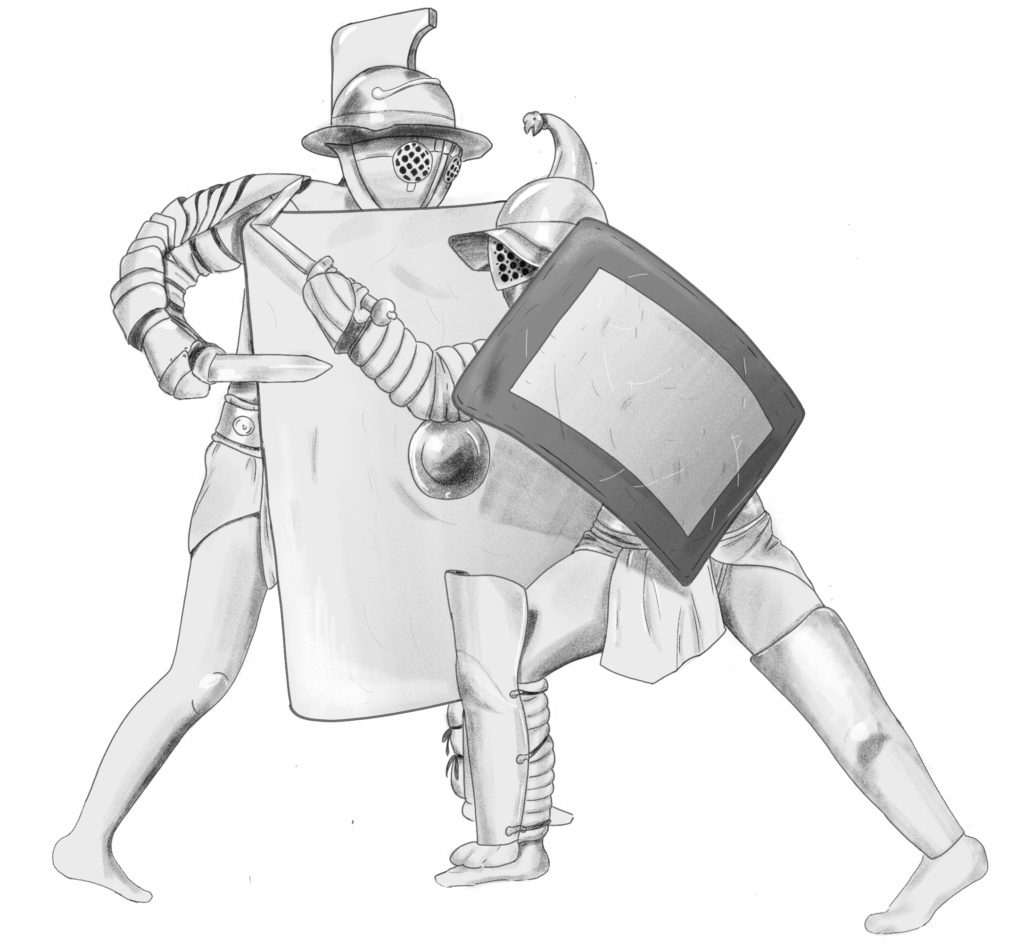

You may have noticed the amazing cover art. This was from Gladiator Doodles, you can find her on twitter (@Amata106 ) and on Instagram (@Gladiator_Doodles )

Here’s the image – thanks so much!

Images.

The image above is of a tomb fresco which has been dated to 370 BC. On the left two boxers fight, a normal event at funeral games. To their right is that image I described with the two fighters.

Photo by Carole Raddato.This one has been dated to the 3rd century BC, but again we have two fighters both with wounds. This is important as it negates the chance that these were ceremonial dances in armour.

from Naples, National Archaeological Museum.Above is a relief from a sarcophagus with gladiators (dated AD 20-50). The procession on the top row and the fighting in the middle row. Note the additional figures, there’s even a couple helping an injured gladiator.

Above you can make out the umpire a bit clearer, this dates to the 3rd century AD.

Above is a drawing of the image I spoke about – the account of the games at Nola.

M Attilius was certainly a talent!

Above is the amphitheatre at Pompeii. You might imagine how close up you got to the fights. This had a capacity of 20,000.

Reading List.

For any classical references feel free to contact me if you need the specific reference.

Beard, M. Pompeii.

Doberstein, W. The Samnite Legacy.

Cooley A & M, Pompeii and Herculaneum: a sourcebook.

Fabiano, Ciardi & Annamaria. Conservation and virtual reconstruction of the Lucanian Paintings from the National Archaeological Museum of Paestum (ITALY)

Fagan, G. Gladiators, combatants at games.

Futrell, A. The Roman games: a sourcebook.

Gerner, D. A Matter of Life and Death.

Goldsworthy, A. Caesar.

Hammond, Beyond the Arena.

Jacobelli, L. Gladiators at Pompeii.

Low-Chappel, S. Bravery in the Face of Death: Gladiatorial Games and Those Who Watched Them

Nossov, K. Gladiators.

Shadrake, S. The World of the Gladiator.

Transcription.

Gladiators – one of ancient Rome’s most iconic elements. But how did it start, how did it change and how were they sourced. Join me as I answer this and more, including fighting stats, on the Ancient History Hound podcast.

Hi and welcome my name’s Neil. So, gladiators – it’s a huge topic so it’s only fair that I manage expectations and explain what I’ll be covering in this episode. I’m going to start at the beginning, with their introduction to Rome and that also means considering where the idea may have come from. I’m then going to give an overview of how it all took of in and out of Rome, how their fights became a political thing and how it all changed as the Roman Republic changed into the Roman Empire and this takes me up to the beginning of the 2nd century AD. Then I’ll take a look at where gladiators were sourced from before finishing up with some aspects to them that you might not be aware of, for example, their fighting stats. I’ll also pick up on a couple of myths, including the whole thumb up or down thing.

In a future episode I’ll be examining the various gladiator types, the specialisations from the commonly known to the niche and I’ll be looking into the gladiator a bit more. It’s a huge topic just getting the basics of how it all developed is quite a tale, as you’ll hear. Just a couple of other points to consider, the first is that this obviously references violence. It almost goes without saying that gladiator fighting was a type of highly violent entertainment alongside beast hunts and executions. This brings me to the second point, the beast hunts and executions were separate thing and won’t be covered in this episode.

Before I start I need to give a shout out to Gladiator Doodles who supplied the drawing of the gladiators for the covert art of this episode. You can find her on instagram where she is gladiator_doodles and on twitter with the handle @Amata106 or just search for Gladiator Doodles.

This brings me on to the episode notes which will include links to Gladiator Doodles, a transcription, images which feature a lot in the episode and a reading list of the sources and works used. The episode notes are on ancientblogger.com – and I’m ancientblogger on Instagram, TikTok, twitter and Youtube. This podcast is also on twitter as @houndancient. So please get in touch, it’s great to hear from you. As an indie podcaster reviews and ratings and so valuable and always appreciated.

And one last thing, as someone who listens to podcasts thank you. I have a backlog and I daresay so do you, so I appreciate you taking the time to listen and I hope you enjoy this episode. Right, that’s it so let’s get started.

When discussing gladiators in ancient Rome the year of 264 BC is the agreed starting point. This year was in fact notable for something far more significant, at least in the short term. This was the year when Rome and Carthage clashed for the first time. It was the beginning of the 1st Punic War and if you’re thinking does that mean Hannibal? Nope, Hannibal and the havoc he visited on Rome wasn’t for another 46 years or so.

Rome at this point was far from the dominating force it came to be. If you went north from Rome you’d find the northern Italian peninsula controlled by Celtic tribes and to south there was still the Greek colonies. In short Rome was a faction on the rise but not the powerhouse it would become.

It was also the year Junius Brutus Pera died, or at least we think that’s who it was because at his munera, the funeral games for a deceased male family member, his two sons exhibited three pairs of fighters. These weren’t referred to as gladiators, the word used is bustuarii and this comes from bustum which translates as funeral pyre or close to it. This small detail is interesting on its own. It underlined the link between the fighters and the funeral games and this is something which early on was where you’d find this kind of activity.

The purpose of the fighters was to appease the manes, the spirit of the deceased but it’s unclear if this meant the fighters fought to the death or simply the act of fighting and the possible bloodshed was enough. In fact there’s not a great deal of detail for this start and how we come to know this date is itself a good example of how pins are stuck in the timeline.

We have two main sources for the bustuarii in 264 BC. The most informative is Valerius Maximus, he wrote in the 1st century AD and recorded that this combat first happened at the funeral of Pera when the consuls Claudius and Fulvius served. He also gave a location, the Forum Boarium or what was the cattle market.

Livy is the second source but it’s a fleeting comment found in a summary of a lost book and echoes the account Valerius gave just without the location.

The first instance of what would become gladiatorial combat is far from what you may picture when someone mentions it. There wasn’t a grand arena, in fact it’s probable that at best a temporary wooden structure would have served as seating for those who watched. As I mentioned the gladiators fighting weren’t even called gladiators and we have no real idea of what they looked.

Even the date itself is, well, not exactly concrete though it is always worth remembering that this is often the case with Rome around this period. We don’t have much in the way of contemporary records. But that said this is what we have and hence the pin in the timeline.

A question you might have is why? Funeral games weren’t themselves a new idea, probably the most famous of these in antiquity weren’t even Roman. In the Iliad there are the funeral games which Achilles threw for Patroclus. These included chariot racing, boxing, wrestling, even archery. And sat amidst them was an armed fight with Diomedes and Ajax which was called off by those watching as things were getting a bit too dangerous. For both Livy and Valerius the notable thing about the funeral games in 264 BC for Junius Brutus Pera was that it involved those paired combatants. So who came up with the idea?

The answer is a firm we don’t know. But it’s a we don’t know…. but and there are two contending options one to the north of Rome and the other to its south.

For the northern option we meet our old friends the Etruscans. These were a people who have been seen as highly influential in the development of Rome. Indeed even one of their mythical Kings hailed from an Etruscan city. When Lucomo arrived in Rome he changed his name to Lucius Tarquinius Priscus and the rest was history. Now if you’ve listened to my podcast episodes you’ll know I’m not scared to mentioning other episodes and this is the case with the Roman Kings. In fact Lucius Tarquinius Priscus gets his own episode. In fairness Priscus was a mythical figure but the later historians of Rome beat the Etruscan drum hard. The toga, curile chair, Circus Maximus and even the Cloaca Maxima these were things with an Etruscan origin.

The link to gladiators is sketchy, both literally and figuratively. A character called Nicolaus of Damascus wrote in the late 1st century BC and noted that the Etruscans featured gladiatorial combat in their banquets. Allied to this are some frescoes on Etruscan tombs which depict fighting possibly in the context of funerals. But it’s not by any means an overwhelming argument, there’s certainly an association of funerals and sacrifice but it falls short of really providing us with anything definitive.

To the south of Rome we also have evidence in a similar format, namely frescoes found in tombs and here we have something far more tangible. The Greek colony of Paestum lies some 300 km to the south of Rome, as I mentioned earlier a Greek colony in southern Italy wasn’t unusual. Many of these came under new owners as the tribes of southern Italy waxed and waned and by the 4th century BC a tribe called the Lucanians seemed to be in possession of Paestum. It’s the frescoes on the tombs which date to the 4th century BC and after which give us what the Etruscans couldn’t, a firm link between combat and funeral.

In some of the frescoes funeral games are had, there’s chariot racing and boxing. One particular fresco, dated to 370 BC, has a pair of fighters. Some detail has been lost to time but we can make out what’s going on. One fighter is reeling from a blow, it’s possible that this is a spear to the head, he falls backwars and blood can be seen from elsewhere on his body. The other figure has his back to us, he seems to be armed with two weapons whilst the other has a shield and spear. Both are naked. Were this image found in Rome in the later period we’d almost certainly consider this in context of a gladiator fight. A later fresco shows another pair of men fighting, both sporting injuries with blood flowing. Unlike the Etruscan frescoes we don’t have to fill in as many gaps, we can argue the context of funeral games is present as the other images around it show just that. So here we have funeral and a combat event.

Added to this we have some later writers who placed gladiatorial contests in this region. Livy wrote of a battle in 308 BC in which Rome fought against the Samnites. Here they were successful and Rome’s allies from Campania, the region in which Paestum is found, forced the Samnites to fight as gladiators at their feasts. This might be much of a retrospective technique, Livy inventing a sort of proto gladiator myth and why it originated from that south. But it wouldn’t be unusual for Rome to be influenced by a practice hailing from southern Italy. Take the whole Roman baths thing, that’s argued as coming to Rome from Campania as well.

Just to recap, we have a sound argument for gladiator-style combat existing 110 years prior to the funeral games at Rome where the bustuarii debuted. As you may know I like to try and give some context to dates, so here we go. That fresco I mentioned which dated to around 370 BC, well, that was around the time that Plato wrote the Symposium and Hippocrates, the father of Medicine, died.

I want to return to Rome now and look into how things changed in terms of the munera and the fighting within it. I know that I’ve used bustuarii but to keep things simple I’m going to use Gladiator which was certainly in use by the 2nd century BC, possibly earlier. And if you didn’t know that’s because they take their name from gladius, the roman word for sword. One thing I want you to do is remember where those funeral games first happened. The Forum Boarium, not an arena, not the colosseum. I would say that there’s a nice link between the Forum Boarium and a mythical fight to the death but I am talking about Rome, a place founded on the back of a brother killing his brother and then the founder being very possibly hacked to pieces. Perhaps the interesting thing would have been to find somewhere in Rome which didn’t have a link to violence.

Anyway, one of the myths about Rome involved a giant called Cacus, he stole some cattle from Hercules which, let’s face it, never ends well. It was apparently in the Forum Boarium, where Hercules killed the giant and it was here that the oldest cult to Hercules was founded in Rome.

The funeral games, the munera of 264 BC must have had an impact because in 216 BC we hear of more involving gladiators. This time three sons of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus upped the ante with 22 pairs of fighters. For those of you with an eye for dates this was also the same year Rome was crushed by Hannibal at Cannae. It’s curious that our first two dates link in with Carthage, perhaps it’s just a coincidence?

There is definitely a link between Carthage and the next instance. In 206 BC Scipio, the famous general, held games in honour of his father and uncle. Not that there had been much of a tradition of gladiatorial games but here we have a number of innovations. The first is the date, the deaths of his father and uncle had occurred some years earlier, possibly 211 BC. Scipio was on campaign in Spain at the time and so perhaps it could be argued that it simply wasn’t practical to have funeral games when they died. However, these didn’t occur in Rome. They were celebrated in New Carthage in southern Spain. Added to this the gladiators weren’t standard fare, again with the caveat that we don’t know much of what standard was. Livy wrote how they weren’t the normal stock provided by trainers or slaves. These men fought willingly. We’ll come to this type of situation later but here it seems as if Scipio was utilising the funeral games and the fighting therein to let local tribes settle some scores. For example, two cousins who disputed a claim over a town and settled the issue through fighting each other.

Politically this was a stroke of genius. Scipio was in foreign territory and the tribes he had on side were only as loyal as they needed to be. In fact Hannibal had the same issue when he had been based in southern Spain. These games must have acted as an important valve and set Scipio as a moderating entity who could facilitate issues which the rival tribes often had.

Back in Rome and in 183 BC Publius Licinius Crassus died and in case you wondered, no, not that Crassus. Publius had been the pontifex maximus, the chief Priest in Rome. Livy wrote that at his funeral there was a public distribution of meat and 120 gladiators fought, presumably that’s 60 pairs. The funeral games lasted for three days so perhaps here we have a slight development. It could have been that on each day 20 pairs fought, because otherwise and forgive the pun, it’s a bit of a case of overkill.

Scipio aside the funeral games in Rome were linked to elite individuals. Men who’d achieved high office and so it’s easy to assume that having gladiators at a funeral was something of a status indicator. Alongside this must have come the burden of expectation, which is very much the issue in our next example.

In 174 BC we hear more about gladiatorial contests and again from Livy. But here we can read between the lines a little. Livy wrote that several small exhibitions of gladiators were given that year and seems to make a snide comment about the big funeral of the year that of Titus Flaminius. Titus had quite a career, he’d been consul and been a successful general in Greece against Macedonia. His death involved funeral games which lasted four days. Amongst a feast and stage plays 74 gladiators fought over three days, but Livy wrote that ‘only 74 gladiators fought’. Was the expectation that there should have been more? What we could conclude from this was that gladiatorial fights were more common and there may have been an expectation of bigger and better.

I’ll roll forward a few decades and to the end of the 2nd century BC. It’s here that gladiators or their trainers may have been involved in training the Roman army. We get this from a comment by Valerius Maximus who wrote that Publius Rufus, a consul in 105 BC, instigated this so that the soldiers were more capable in both dodging and delivering blows. Whether this happened or not is debated but it did fall into a wider change in the Roman army, the Marian Reforms where Rome went from an amateur army to a professional one. I should give a wider caveat that how the reforms happened and whether they all occurred under Marius is debated. But aside from this it would have made sense to have gladiator trainers or gladiators doing exactly this.

Roman soldiers were drilled in combat but also in fighting as a unit. Gladiators weren’t they were one-on-one specialists so perhaps there had been a gap in technique observed by those in charge. Gladiators, or their trainers could certainly fill in as a particular skills coach might do in a modern sports team – offering specialist training to develop the soldier further.

Moving to the first century BC we meet a number of famous characters from Rome. This was the century of Julius Caesar, Mark Anthony, Cicero and towards the end of it the change from republic to empire with Augustus as the first emperor. The gladiator and the spectacle of the gladiator was moulded by the political changes and demands of this period but I’ll start with the more tangible and by that I mean where the fighting took place.

One of the biggest contrasts between how it all started and where it all ended up in terms of the gladiator is probably found in where you could watch it. At the outset the fights took place in secondary venues, by that I mean there wasn’t a designated place. There was the Forum Boarium and the saepta a building in the Field of Mars which was normally used for voting. In a way this is why it’s difficult to know much about the fights at this time because there wasn’t a specific venue for them.

In 52BC the first amphitheatre was credited at Rome, this was wooden and apparently formed of two theatres which wheeled round to face inwards, creating an enclosed space. Wooden amphitheatres became the standard and this was primarily because of the nature of the events, they were private games for funerals so there wasn’t an inherent need for a permanent structure which everyone could use. That changed in 29 BC when Statilius Tarus built the first stone amphitheatre. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64 so we don’t have it but it’s thought that it would have been located on the Campus Martius, the Field of Mars which is where other fights took place.

To find the earliest stone amphitheatre we need to travel to Pompeii where one was built around 80 BC. In fact the consensus is that it was the south, again, where the amphitheatres were first found. Of course when I talk about amphitheatres one looms large, the Colosseum. This wasn’t built till AD 80, some 344 years after those first funeral games I started with. If anything the Colosseum was the pinnacle of the Roman manifestation of the gladiatorial experience and I’ll come to that later but it’s worth noting just how much time had lapsed between those first recorded fights and the famous building which is often seen as the embodiment of the gladiator in Rome.

The first century BC was one in which the political situation really heated up in Rome, political careers were even more cutthroat than they had ever been and the thing about gladiatorial events was that they were becoming increasingly popular. It was a very effective way for a politician to make a name for himself at Rome. So it’s no surprise that Julius Caesar stepped forward and, well, you’ll hear. In 65 BC Caesar had started out on the political ladder and a set of gladiatorial games were just the trick. Except there was one big problem with them. As you’ll recall these were part of the funeral games the munera for a dead male relative. So Caesar hosted some for his dead father. A father who had died 20 years earlier. Ahh, Julius.

Caesar went further, in 45 BC he had 320 pairs of gladiators fighting in games thrown for his dead daughter. The fact that she had been dead 8 years, tragic though that was, gives you an idea of the rationale but perhaps more controversial was that this was the first funeral games given for a female relative where gladiators fought.

The gladiator was now a political asset, spectacles involving them could be used to build a support base. Needless to say this got many people a bit twitchy and those in power looked to limit this political tactic. A law of 65 BC limited the number of gladiators which could be kept at Rome and we are told by Suetonius that this resulted in fewer fights at Caesar’s games. A few years prior the Lex Calpurnia had prevented the use of seats at games, gladiatorial contests and theatrical performances for political cannvassing. In 63 BC Cicero’s Lex Tullia prevented those seeking office from giving games at all.

It’s important to note that these laws related largely to the games which were separate at this point in time from the munera, the funeral games where gladiators fought. But they were part of the same political toolkit, particularly for ambitious Roman politicians and ruthless ambition was often the default setting for any Roman politician.

There was also some concern over gladiators out of the arena. In a letter to Quintus in 49 BC Cicero raised the issue of a certain Julius Caesar and his gladiatorial school in Capua, southern Italy. Cicero noted the concern over the 5,000 ‘shields’ at the ludus, the gladiatorial training school. The response was that these gladiators were broken up and distributed away from the ludus. This may have been prescient as it was this year that Caesar crossed the Rubicon and marched on Rome.

Another way gladiators could be a threat was their use by politicians as bodyguards or followers. The likes of Milo and Clodius had their own entourage and these clashed, famously in 52 BC it led to Clodius being killed.

Of course, when you are on the topic of gladiators getting out of hand I need to at least briefly mention the most famous instance of gladiators out of control. Spartacus. This will certainly require an episode of its own but in 73 BC around 70 gladiators broke out from a school in Capua, that’s in the south of Italy. Over the next few years Spartacus fought against Rome and etched his name in history, though we know very little about him. The “I’m Spartacus” thing, that was pure Hollywood.

Towards the end of the 1st century BC Rome underwent a huge political change. Out of the smoking ruins of yet another civil war Octavian took control in 31 BC. He later renamed himself Augustus and was Rome’s first emperor. The reforms of Augustus were widespread and touched everything. Gladiators were included – where previously their fights had been kept within the munera, the funeral games, now they were incorporated into Roman games full stop. Roman games had been a thing unto themselves since the early days of Rome. They might involve theatrical performances, chariot races and even beast hunts. In a way folding the gladiatorial fights into them made sense. A pattern now formed with beast hunts in the morning, executions in the arena at midday and the gladiatorial fights in the afternoon.

But this was Augustus and therefore it was political as much as practical. Augustus must have seen how potent the gladiator fights were as a way of garnishing popularity. As part of the games the emperor and therefore the state now controlled them. Outside of Rome they could occur but only through a magistrate, so it was always at the approval of the emperor that these took place.

In the 1st century AD the Imperial grip on what was an industry, tightened further. The basic business model had been for the organisor of the games which involved gladiators to lease them from the ludus. This could be expensive as the better record a gladiator had the pricier he was. This itself links in with the idea that notable gladiators were less likely to be killed in the arena, because it would incur the organiser of the games even more of a cost.

By the time of Trajan in the early 2nd century AD Rome had four large Imperial gladiator schools. These allowed the emperor to avoid the costs of hiring in the talent but this didn’t totally excluded it. There was still the need to supplement and bring in gladiators from afar and the regional fights still required the gladiators to be supplied from closer to home. The most famous imperial gladiator school the Ludus Magnus was built in the late 1st century, under the emperor Domitian. This literally fed gladiators via an underground passage into an amphitheatre which had only recently opened in Rome. Of course I’m talking about the Colosseum.

The Colosseum took 10 years to build and opened in AD 80. Estimates of its capacity range from 50 – 80 thousand. It’s oval shaped arena measured 83 metres by 48 metres at its widest point, that’s 272 by 157 feet. To get some perspective it’s large but you wouldn’t be able to fit a modern day American football field in there, even taking into account the fact that the latter is a rectangle.

This venue took over and gave Rome a definitive location for its games. But in a sense Rome was lagging a bit. Pompeii had a permanent venue, a stone amphitheatre which held 20,000 people back around 70 BC. We’re talking 150 years prior to the Colosseum. Presumably the smaller venues had sufficed until that point.

When considering gladiators Pompeii is a great place because we can find reference to the gladiator on the walls in the form of adverts for games and even the results. Take Aemilius Celer who posted an advert about games involving 30 pairs fighting over 5 days. Not only did he add his name but also that he did this at night, perhaps that was the standard. You’d wake up one morning and see what games were planned on the walls, again, perhaps there was a particular area known for these adverts. It wasn’t just games at Pompeii which were advertised, graffiti for games elsewhere has been found, for example for those at nearby Herculaneum. Whether inscribed in bold letters or just a scratch a pattern can be observed which gives the dates, the location and the numbers of gladiators fighting. Usually the person staging the games also features.

It wasn’t just upcoming events which were drawn and written on the walls at Pompeii, it could also be the results of those games.

Outside the city walls on a tomb by the Nucerian gate a set of drawings were found. These seem to record a set of games at nearby Nola and they provide a wealth of information. The drawings comprise of three levels, at the top is the most detailed drawing. On it a pair of gladiators fight and are flanked by musicians. An inscription reveals the sponsor of the games, Marcus Cominius Heres and that they lasted four days and occurred at Nola.

The drawing provides a lot if information about the pair of gladiators in the centre. Each is named, we have Hilarus and Creunus. Next to the name of Hilarius the letters NER probably relate to Nero and that Hilarus was from the Imperial gladiator school. Both have roman numerals next to their name and these are their fighting records. Hilarus has fought 14 times with 12 wins, Creunus 7 times with 5 wins. Under the name of Hilarus there is a V which indicated he won the fight, Crenus too has a letter, M which shows that he lost but was reprieved.

Below this are two more pairs of gladiators with stats and the result of their encounter. M Attilius beat Hilarus who was reprieved and he did this on his debut, the letter T indicated tiro, meaning it was Attilius’ first fight. Hilarus also has his record, 14 fights 13 wins so it’s plausible that either this was the Hilarus in the top row and the stats were mixed up or it was a different Hilarus.

Below this the final pair include M Attilius again this time facing off against L Raecius Felix. This time Attilius has his 1 for 1 stat next to his name so presumably this was his second fight. He’s victorious again though the V next to his name is inconsequential as his opponent kneels before him with his helmet on the floor. As with the previous fight the loser was spared and this was Raecius’ first defeat as his record was 12 fights 12 wins up until that point. These drawings are fascinating because we get a rare glimpse of the fighters themselves, I wonder for example was the knocked off helmet an embellishment by the artist who drew this or had they been there and this actually happened in the fight?

These drawings supply a rare insight into the world of the gladiator and also not just that – they allow us the consider how they were received by the people who watched them. These images weren’t created by some highly paid artist as a fresco or mosaic in a villa. This is much more a personal response, a record which someone drew presumably to communicate to those passing by. If you’re a tad confused by that, after all it was on the side of a tomb, well tombs were often found alongside roads. This was outside the Nucerian gate so we can suppose that there was plenty of footfall. The interest in records gives us the idea that these were communicated to the public both before and after a fight. Perhaps they were on the adverts that went up on the walls and, as with the tomb, recorded afterwards. This makes sense, if you’re generating interest in the fights or you just want to have people talking about them.

There’s something else that the drawings state, a point which I haven’t so far made. Namely that gladiators fought in pairs. It wasn’t a mass brawl and we can get more of an idea of how things went down in the arena from other pieces of evidence.

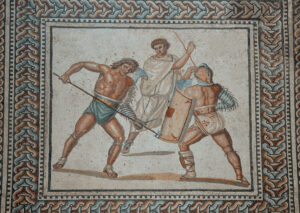

A sarcophagus dating to the early 1st century AD featured a frieze with a set of games including gladiators. The middle row shows not just gladiators but what seem to be attendants and umpires. Later mosaics show this more clearly with an umpire between or behind the two fighters. To use a modern analogy, this seems to move away further from the idea of a back alley brawl and into something akin to a fight in the boxing ring. There was an umpire and expectations, perhaps extending to one fighter stopping when it was clear the other was beaten and then waiting to hear what would happen next to the defeated.

Given the immense popularity of the fights by the 1st century AD you might be thinking where exactly gladiators came from? At a guess you’ll probably think of prisoners of war and that was certainly true. But slaves could also be sold to a gladiator school or sent to one by their master. Added to this were the criminals. I should add a slightly macabre detail here because a criminal could be sentenced to the games or to the gladiator school. The former was a straight out death sentence, you were there to be publicly killed. The latter may not have sounded much better but there was a silver cloud. A criminal could earn his freedom after 3 years of being a gladiator. The caveat was that you had to survive.

There was another way gladiators were recruited and this is possibly the most curious – volunteers otherwise known as auctorati.

Unlike the slaves or prisoners of war these were freeborn men who would sign a contract and effectively hand themselves over to the gladiator school or lanista they joined. They were owned now, like the other gladiators they might die in the arena or even in training. At best this feels like a situation borne from desperation and perhaps it was. Upon signing the contract they were awarded a sum of money and presumably they could earn more with successive victories. In the 1st century AD Tacitus wrote how the emperor Vitellius issued a strong warning against the equestrians, the equestrian rank in Rome from degrading themselves by fighting in the arena. Presumably they did so through this route.

One obvious motivating force was probably debt. This is something Juvenal railed hard against in his 11th Satire. Here he lands a few jabs on the rich young men who have spent too much, often including their parents wealth. What followed was a trip to the gladiator school to sign up to appease their creditors. Juvenal also mentioned the tribune, because a freeborn Roman needed the tribune’s approval before he could sign yourself up to fight.

The presumption is that after fulfilling the contract an auctorati could be free again, and the route to freedom through the rudis, the awarding of the wooden sword was something which must have been the goal of anyone in the gladiator school. But anyone who made it out wasn’t likely to ever have the life of a citizen, gladiators were placed in a category of persosn known as infames. Anyone in this situation had no real legal rights, and this can only have resonated with those who previously had any, presumaly the auctorati. In short an ex-gladiator would find life tough and some sold themselves back into a ludus or gained employment as trainers.

The auctorati might have a slightly different experience with the ludus they were training at. It’s possible that they weren’t required to live there – the caveat being that they needed to train and fight and there was that contract. Life in the ludus was basic, the gladiator school at Pompeii had enough room for two men per cell. They most likely slept on straw beds which was actually not as linked to poverty as we might think it today. Their diet mostly consisted of cereals, in fact they were nicknamed the barley-men by Pliny the Elder. I’ve heard this pulled into discussions about vegetarianism and the like. I suspect it has nothing to do with this, it was that barley was cheap and meat was expensive. That said this runs the risk of generalising a bit too much, perhaps the more valued fighters in a ludus might get meat on occasion as a treat.

It’s important to remember how gladiators were considered. As assets and like any asset their care was linked to how much they were worth. This extended into the realm of healthcare, a ludus would most likely have some form of healthcare facility. In a larger ludus this might be a surgery with a full time specialist who would treat the types of wounds a gladiator might get.

This brings me to a question often debated. How dangerous was it? A reform Augustus included was prohibiting fights which were to the death and you’ve heard me mention the examples of Hilarus and Raecius who both lost but weren’t killed. Estimating your chances of surviving as a gladiator is almost a an impossible thing to do, there are so many factors to include. You might lose and not be killed, or lose and die of your injuries even if spared. Georges Villes attempted a study on this for fights in the 1st century AD and ended up with a number of 19 fatalities per 100 fights. What’s argued is that in the following centuries the chances of a losing gladiator being killed increased as the crowd became more demanding of the fighter on the losing side. It wasn’t enough to be plucky any more.

And on the subject of death it’s in this context that we get some insight. Tombstones of gladiator have been found and these can tell us a lot. Take this one for example:

“To the revered spirits of the dead. Glauco, born at Mutino, fought seven times, died in the eighth. He lived 23 years 5 days. Aurelia set this up to her well-deserving husband, together with those who loved him. My advice to you is to find your own star. Don’t trust Nemesis, that is how I was deceived. Hail and Farewell”. CIL, 5.3466.

End quote.

Other tombstone inscriptions have the other fighters from the gladiator school contributing to the burial costs and it gives you a sense of camaraderie there. An issue with these is that it’s not always possible to know when they dated to, presumably those married had been freeborn and married before they became gladiators. The tombstones also indicate how many fights and this is obviously a major variable and a paradox. The more fights a gladiator had the more likely he was to die but contrastingly the more experience he got and the better he became at it.

The context of relationships brings me to something of a trope, namely that gladiators had the noble ladies of Rome and elsewhere swooning. It’s a sweeping generalisation and informed by a couple of instances which need a bit more context. Take the infamous discovery of the skeleton of a noble woman in the gladiator school at Pompeii. This has been often used to support the idea that she had been caught having an affair. Yet the cramped room she was found in had several gladiators and a dog. The more likely situation was that she had been out in the open space during the eruption and ran for cover, perhaps like the dog. Then there’s a couple of inscriptions about a certain Celadus, again at Pompeii. In two separate inscriptions Celadus is both the sigh of the girls and the glory of the girls.

Wow you might think, this Celadus was obviously popular. But then, as Mary Beard, noted you find out that the inscriptions come from inside the gladiator school in Pompeii. So there’s the possibility of wishful thinking or just a bit or ribbing going on.

Of course gladiators represented a taboo, though they were admired for their courage in some quarters in a social context they were no better than pimps, prostitutes and dare I say it. Actors. They sold their flesh so they could be popular but on a moral level they weren’t admired. When Juvenal mentions the wife of a senator running off with one it’s as much a possible reality as simple another gripe Juvenal has with the awful state of things. Juvenal spent much of his time bemoaning his life and how Rome was full of slaves richer than him. This could be just another instance of the corruption of society as much as it was a regular occurrence.

To counter this human history has shown us that taboos can attract attention. So perhaps in some instances an encounter with a gladiator occurred from a Roman man or woman. In fact it would be surprising if this didn’t happen. What we lack is any female perspective.

Up until now I’ve spoken about gladiators as a monolithic bunch. But of course they weren’t. They fought with various weapons and within a set speciality, as I mentioned at the beginning I’m going to do a minisode just on the various types because it’s certainly worth unwrapping and this will include female gladiators.

As we come to the end of the episode it’s time I tackled the who thumbs up-thumbs down thing. The answer is that we just don’t know. It’s Juvenal who referenced the use of the thumb but doesn’t specify what gesture either spared or doomed a beaten fighter. It’s ironic that probably one of the most famous things about gladiators is something that we really can’t confirm. Trust me when I say this is the kind of thing that you meet elsewhere in ancient history. Something just captures the imagination and you spend a lot of your time waggling your finger, or thumb, and trying to say to people “hang on a sec we just don’t know”.

And with that I come to the end of the episode. I really hope you’ve enjoyed what I have been talking about and taken away a few things that you didn’t know. Now if you want to go and find those episode notes on ancientblogger.com feel free to check them out. More importantly look after yourself, take yourself away from it. It’s a pretty hectic time of the year – take the pressure off

Till next time keep safe and stay well.