I hope you enjoyed the episode on Archaic Athens and Democracy and here are the episodes notes I mentioned. I mentioned a few other episodes I have done – these can be found on my Ancient History Hound podcast. You should be able to find it on most platforms.

Demes and Attica.

In the episode I mentioned Attica, the region which Athens controlled.

Here’s a wider map of ancient Greece (you can see Attica on it).

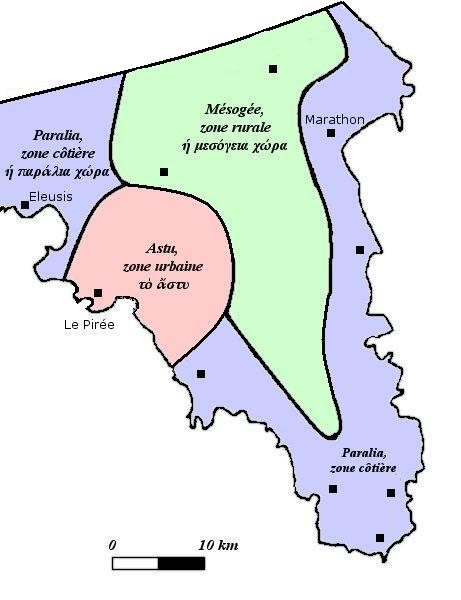

Below is the region of Attica and how Cleisthenes divided the region into three areas, City (pink), Inland (green) and Coastal (blue). A good link to more on this is on the Wiki entry for demes.

I also mentioned the complex mixture of demes and tribes and tried my best to explain it. Demes were grouped together from their region, these were known as trittyes. There were 30 of these trittyes in total. Each of the 10 tribes was composed of one trittye from the coast, one from the inland and one from the city.

Tribe = Trittye from the coast + Trittye from the inland + Trittye from the city.

Harmodius and Aristogeiton – heroes of the democracy?

The above statue is very famous and depicts the pair in their heroic exploits to rids Athens of tyranny. It’s know and the ‘tyrannicides’ and its a Roman copy of a Greek original.

The act was also the subject of this vase by the Syriskos Painter (circa 475–470 BC).

Professor Edith Hall and Cleisthenes.

I cited Professor Hall in the episode, here is her talk on democracy. It’s brilliant and one day I hope to have her on my podcast.

You can read more about Professor Hall on her website here.

Reading List.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War.

Herodotus, The Histories.

Plutarch, Lives.

Blok, J. Patronage and the Pisistratidae.

Cartledge, P. Democracy.

Dawson, S. Rethinking Athenian Democracy.

Gouschin, V. Pisistratus’ Leadership in AP13.4 and the Establishment of the Tyranny of 561/60 BC.

Harris, E. Solon and the Spirit of Early Greek Law.

Kagan, D. Pericles of Athens.

McGlew, J. Tyranny and Political Culture in Ancient Greece.

Sagstetter, KS. Solon of Athens: The man, the Myth, the Tyrant?

Zatta, C. Making History Mythical: The Golden Age of Peisistratus.

Transcription of the episode.

(some parts of the intro section were ad libbed but the main part whould be accurate)

Tyrants, fancy dress political campaigning, a juicy building contract and Spartans. Join me as I talk about how democracy took hold in Archaic Athens on the Ancient History Hound podcast.

Hi and welcome, my name’s Neil and in this episode I’m unravelling how the political landscape in Athens changed immensely in the 6th century BC and how it ended up with a new political system there which it ultimately became famous for. I’m going to give an overview of what that was exactly but this episode will largely be about the people and situations before. Trust me when I say that some of them, actually well, I am not going to spoil it.

Before I start the standard spiel of where you can find me. On twitter, instagram, tiktok and youtube I’m ancientblogger – it’s all ancient history content btw. I also have a website – ancientblogger.com and here you’ll find notes for this episode. This will be formed of a reading list of the sources used, a transcription of the episode and some maps and images as well as any supporting information which will help you get a bit more out of it.

Oh, and this podcast has its own twitter as well, @houndancient.

If there’s a chance you can leave a review that would be fab, this is a hobby, I don’t have a marketing budget so reviews and reccomends are all I have. To all new listeners, I hope you enjoy what you’re about to listen to and to returning listeners, thanks I really appreciate you coming back for more punishment.

Just to be aware there are a couple of caveats. The first is that the period I’m covering is the 6th century BC, so all dates are BC, I normally say BC, but just in case. The second point is that I’ll be talking about citizens and political participation. Citizens in Athens meant men over a certain age, so when I talk about citizens that’s who I’m referring to. You probably know this but just in case.

With that covered I can begin.

In 508 BC Athens had a democracy of sorts in place. This itself has been debated and I’ll pick up on that later on. But it didn’t appear out of nowhere, a fascinating range of events had led up to its emergence and adoption. Some more incidental and others we can tie more closely to it. What I’m going to do is turn the clock back, back to the beginning of the 6th century BC and to a crisis shaking Athens.

The crisis in question related to a widening gap between the rich and poor, particularly the poorer tenant farmers. The nobles who owned the land were making ever more harsh demands of them. Many of those tenant farmers or even ones who owned small lots of land were finding themselves in debt and this had a couple of very nasty outcomes. The first was something called debt slavery where you existed to work off any debt you had. Though temporary you might envisage a situation where it became near impossible to work yourself out of what was an economic form of slavery. You were essentially trapped.

The second was literal slavery, a creditor could sell you or members of your family, usually abroad – as slaves. The idea that if you were a citizen of a city state such as Athens you could not end up a slave was not the case. In fact freeborn people ending up as slaves was more common than you might think, if you’ve listened to my episode on Piracy you’ll know exactly what I mean.

With that said the nobles weren’t entirely comfortable with the situation either. Perhaps they feared mass civil unrest or the outbreak of tyranny. Something needed to be done and in 594 BC the Athenians elected a figure called Solon to the position of Archon to sort it all out.

Solon is an intriguing character, a noble born in Athens who took up trading and travel. He was a notable poet and in fact we know of his political contributions because he referred to them in his poetry. The reforms he put in place became famous in antiquity, though it’s not always clear if he enacted all of them or whether some where later credited to him. These reforms touched upon everything, across the legal, political and social. Even to the private. According to Plutarch, albeit writing centuries later, the new husband of an heiress was required to, shall we say, perform his duties at least three times a month.

But back to the crisis, there were two main reforms which are of particular relevance here.

The first involved the creation of 4 classes which now defined a citizen’s status by their wealth, and this was linked to their agricultural output. The fantastically named Pentacosiomedimnoi were at the top with the Hippeis second and the Zeugitae third. At the bottom was the class called the thetes. These would probably have formed the majority of the Athenians living in Athens and in Attica which was the region in which Athens sat. In fact it’s an important point to remember that though I say Athens and Athenians we’re really talking about the region of Attica because it’s there where these changes manifested as well. The majority of the population lived outside of Athens and in the small towns and viallges around Attica.

These 4 classes gave differing levels of access and participation to the new political organs Solon put in place, though I should add it’s not entirely clear what these new political organs were. But you get the idea. It seems that the top political offices were reserved for the two wealthiest classes with the zeugitai, the third class, given some minor offices. The only class who didn’t have access to any of the offices were the Thetes. But they got some choice concessions. It seems that they could vote in an assembly, they also got access to a court where they could appeal decisions. But they also got a huge break and it was called the (see-sak-thee-ya) Seisachtheia or ‘shaking off the burdens’. This was a cancellation of all debts. And for a moment just think about that, perhaps even imagine that now! In addition Solon banned the practice of debt slavery.

Both the poor and the rich got something of what they wanted, but not as much as they’d hoped. The nobles maintained their grip on power through the offices of state and running the main council. But the poor now had economic freedom and a sliver of political participation. However, this wasn’t enough and like any good mediator Solon was not popular in Athens with either side. After his reforms he left Athens for 10 years and it’s been argued that this was to ensure he couldn’t effect or take advantage of the situation there. But also perhaps because he was very good at reading the room.

What Solon had created was a timocracy, not a democracy. A timocracy is a a type of government where only property owners could participate or where access is through owning property. So why have I mentioned it at all? Well, there are a couple of reasons. The first is that this event is often linked to the events much later on. They also broke the control the nobles had over power. True a rich person was often a noble, but it allowed the door to political power to be opened by a fraction. In theory someone born outside the nobility could amass wealth and gain access they would never have had.

There are also some elements of Solon’s reforms which are built upon or referenced when democracy was later established. Many of his reforms, particularly the legal ones were kept well into the period when Athens had its democracy. Looking back Solon’s actions didn’t result in a democracy but they enabled the changes which would lead to it – particularly in the concept of everyone having some involvement. The basic concept of participation.

And it’s possible that Solon’s big idea of wider participation was something in the wind at the time because elsewhere in Greece there’s evidence of participation in politics. A good example of this can be seen on a stele from Chios which has a reference to a council where people have their say.

What next then for Athens after Solon was gone? Well, his structures stayed in place and though these resolved the issues they didn’t prevent a type of situation which occurred and would come to dominate much of the remaining century at Athens. This was a tyrant.

Tyrants were a political feature of ancient Greece. What made a tyrant wasn’t always easy to define as we in the modern period experience the word as a pejorative. Don’t like your boss or someone in your family. Yeah, they’re a tyrant. But the actual definition of a tyrant was a slippery one in the archaic period. The general consensus was that it was someone who seized power in a city state, normally through non-standard means, often a coup or some sort of violent uprising, and then they ruled the city state in the manner of a king and with no checks and balances.

This all sounds bad stuff, but tyrants could also do plenty of good things. Polycrates at Samos raised the Island’s profile immeasurably and improved the city with works. Likewise the tyrant we’ll hear about at Athens was most likely very popular amongst the common man because he invested a lot into raising Athens up and making it a popular place.

Of course there could be tyrants who behaved badly towards their people but usually the type of person who’d have the biggest gripe with a tyrant would be a fellow noble. If you weren’t from the tyrant’s family it could mean at best being denied the power you once had or at worst you could lose everything. In a way a tyrant as a bad thing was subjective. Perhaps that’s why Aristole didn’t refer to a ruler called Pittacus as a tyrant but the poet Alcaeus did. And perhaps the reason why Alcaeus called him that was because Alcaeus was one of those political rivals who lost out when Pittacus seized power.

Around the 560s factions had started to form at Athens, each greedily eyeing the other up. The three main contenders for power were Megacles, Peisistratus and Lycurgus. I should clarify that this is not the Lycurgus associated with Sparta and in fact you can forget about him. The more interesting were Megacles and Peisistratus.

Megacles was from an infamous family, the Alcmeonids. These had been part of the nobles for some time but many years earlier, around 632 BC, had behaved in a very un-noble way. A group had made a power grab in Athens, failed and had sought sanctuary in a temple. This was an agreed convention in ancient Greece, anyone seeking sanctuary couldn’t be removed by force and to do so was a big taboo. The Alcmeonids didn’t remove the party involved, negotations had resulted in a truce with the party leaving Athens. However, as they left members of the Alcmeonids pounced and killed them. This act was to leave a stain on the family, one which wouldn’t be forgotten and will come up later in this episode.

Peistratus was from a similarly noble family, but without the stain though as you’ll hear he didn’t exactly play clean.

In 561 he made his play for power and I choose the word play because Pesistratus was all about performance. He’d already been a successful general and was popular with the masses but one day a wounded and beaten Peisistratus drove his chariot into the agora in Athens. He pointed to the cuts and bruises on his body and told the astonished crowd that he’d been ambushed by his political rivals and been lucky to escape alive. What he needed was a bodyguard which would keep him safe and certainly not be used for, say, any nefarious activities.

The appeal worked and he was given a bodyguard. You can guess the rest, using these men, armed with clubs – a detail I’ll come to in a moment. Peisistratus seized power.

This famous account, by Herodotus, is a curious one. It’s more than plausible that it acts as a sort of summary. There may have been a number of small and complex political moves which went on but a tale such as this is a better story and one which sticks in the mind. Of course it could have happened but perhaps there was more to it than just this. Peisistratus seemed popular with the masses as I mentioned so a small band of armed men was really all that was required as it was the rival nobles who needed to be gently persuaded as to this.

There’s an interesting comment on the weapons the bodyguards wielded. Why clubs and not spears? It’s possible that this was symbolic with Hercules or Heracles famous for having one. The hero used his as he pacified and brought order to the world of myth, so perhaps this was a nice piece of PR. The bodyguards are’t here to hurt anyone, just bring some order.

Impressive though it was the rule of Peisistratus didn’t last long at least initially. Around 556BC he was driven from Athens but he soon returned, his political opponents may have had a common enemy in him but now they fell about each other until one had a great idea. The great idea belonged to Megacles who I spoke of earlier. Perhaps realising that Athenian politics was just too fractured he suggested an alliance with Peisistratus. The cost of such an alliance was that Peisistratus would marry his daughter and so it was agreed. All that was left was the right type of political campaign or what we might call rebranding.

This involved a very tall woman called Phye. Peisistratus dressed her as the goddess Athena and she drove about Attica and Athens saying how Peisistratus was bringing her back to Athens. A sort of Make Athens Great Again. And it worked. Herodotus perhaps unfairly commented that the Athenians were stupid to believe this, but perhaps he missed the nuance. Peisitratus knew that it was the poor who he needed to appeal to and he did exactly that. Did a bunch of poor farmers in a village believe this woman was Athena? Probably not. Did they get the message – that here was someone who would look out for them and give them some civic pride. Yes they probably did.

The political marriage between Peisistratus and the daughter of Megacles didn’t go well. The main issue was that Peisistratus didn’t want children with someone from the Alcmeonid family what with their stained reputation and all. Peisistratus was again driven from Athens but again returned, this time in 546 BC and after a battle. No political gimmicks this time.

Peisistratus ruled till 527 BC and his time in power, including those shorter instances, was notable for what he did and didn’t do. He certainly repayed the poor for backing him, in some instances offering loans. But he also set about raising the profile of Athens. A great example being the establishment of the Panathenaic games.

This was Athens’ answer to the Pan-Hellenic games which featured at Olympia, Delphi, Corinth and Nemea. They were hugely popular, people travelled from all over Greece to attend them. So why shouldn’t Athens have its own games? Naturally the games at Athens were curated to promote the city and its people as much as it could. It would also look inwards and work to further embody a sense of city pride. For example, where the Pan-Hellenic games had events open to all Greeks some of the events of the Panathenaic Games were restricted to Athenians alone. The games at Athens were also chrematic, meaning that their was monetary value in the prizes. You didn’t win fame and a wreath you won amphorae of olive oil – which were very valuable. It was a festival soaked in pomp and ceremony relating to Athens. It was a huge PR win. Elsewhere he built new buildings and encouraged the arts. The poor farmers had loans and were encouraged to grow olives as part of a wider policy of exporting oil.

All of this moves to a point I made earlier about tyrants being good for city states, at least in some aspects. The average poor Athenian had new experiences in the city and a leader who seemingly had their interests as well as the city’s as a driving belief. Of course the nobles, albeit those outside his family or not in his immediate circle, had less but perhaps they were also happy to sit on the sidelines. What’s notable is what he didn’t do. There’s no evidence that Peisistratus changed the political structure, he kept it. To be fair he staffed his followers in key positions, thus shoring himself up. He may have acted the king but he was clever enough to make it look as if he wasn’t.

In 527 BC Peisistratus died and his elder son Hippias took over, things ticked over until 514 BC when an assassination changed everything. It wasn’t Hippias who was assassinated but his brother Hipparchus.

The rationale behind the assassination is a tale in itself which I’ll get to at the end of the episode because it’s a great example of history being rewritten more or less at the time – but the immediate effect was that it caused Hippias to become the sort of of tyrant which gave tyrants a bad name. Who would save Athens from this increasingly unstable ruler? Perhaps who you might not think, it was the Spartans.

It wasn’t out of the goodness of their warm Laconic hearts that the Spartans, led by their King Cleomenes, drove Hippias from Athens. The exact reason isn’t clear but Herodotus recorded that whenever a Spartan visited the Oracle at Delphi the response would be for them to set Athens free. This messaging stuck fast with Sparta which was notoriously pious. In 510 BC King Cleomenes entered Athens and beseiged Hippias who was holding out on the Acropolis. Eventually a truce was agreed and Hippias and his family left for Sigeum in what is modern day Turkey. He wasn’t completely out of the picture though and we’ll hear more of him later.

With Hippias gone we meet an individual credited with the setup of democracy a few years later, the famous Cleisthenes. He was the son of Megacles, who you will remember from earlier. Exactly how Megacles and the Alcmeonids had fared during the return of Peisistratus is debated, Herodotus thought that the entire family had been exiled, except an inscription has been found which points to Cleisthenes being an archon at Athens. Perhaps the Alcmeonids had settled for their place in Athens but they’d also not given up their political amibitions. It had been Cleisthenes who had won a building contract at Delphi for a temple. Rather than simply fulfill the contract the job was done above and beyond. Though the specifics hadn’t demanded it the finest and most expensive marble was used, despite not being charged for.

Surely it was just a coincidence then that the very place whispering demands in Spartan ears to remove Hippias from Athens was in receipt of a huge favour from Cleisthenes whose family would benefit from such an event. It certainly didn’t escape the likes of Herodotus who called the rebuilding of the temple at Delphi by Cleisthenes at outright bribe.

With Hippias gone you may have thought that the road was open for Cleisthenes to take control of Athens, except, as ever in Athenian politics, there was always a rival. In this case it was a man called Isagoras. Like Cleisthenes he was a fellow noble and the two faced off against each other with their respective supporters. The issue was that neither had enough support to secure a political victory.

That was until Cleisthenes brought the poor onto his side, by poor we might think of the thetes or certainly the lower classes. For some reason these hadn’t been given much attention and by appealing to them Cleisthenes now had the bulk of support.

As Cleisthenes had tipped the balance with this new base it fell to Isagoras to return the favour and he did this by turning to Sparta. In fairness this wasn’t the worst idea, after all Sparta would certainly be happy with a friend in place at Athens and they had just removed a tyrant from there. In 508 BC Sparta again entered Athens but this time to support Isagoras, Cleisthenes and his supporters fled and Isagoras set his mind to a brutal change of things. The Council, well, that had to go and instead 300 of his closest supporters would suffice in its place. Except Athens resisted, the Assembly was furious and soon civil revolt broke out.

The outcome was Isagoras and the small Spartan force retreating to the Acropolis and now they were under seige. Eventually a truce was achieved with Isagoras and the Spartans allowed to leave. Cleisthenes now returned with what amounted to a political blank cheque. Though Athens now celebrated it was also in grave danger – Sparta was now technically at war with Athens and the latter searched round for any allies and eventually they found a backer who might help them balance things at least in terms of finance, the Persians.

I understand that you might want to have a sit down and a nice cup of tea. In a short time you’ve heard that Sparta helped Athens be rid of a tyrant and now Athens was in league with Persia.

We think of this now as somewhat laughable, but at the time it made sense. Athens must have been seen as ripe for the plucking and Persia wasn’t the enemy it was to later become. Ironically this request for aid from Persia was going to have consequences down the line for Athens and I’ll mention this at the end of the episode.

So what did Cleisthenes do? What were his reforms and were they that democractic? I’ll start with the first question. One of his more substantial pieces of work had probably already happened and Herodotus links it with him winning over the thetes or bringing the poor onto his side when tipping the balance against Isagoras. It was a complete social upheaval and even changed the way people referred to themselves. The establishment of the 10 tribes.

Up until this point there had been 4 tribes in Athens. But Cleisthenes, and presumably his advisors, dismantled these and in their place were now 10 tribes, each named after a hero. These tribes were formed of trittyes, or thirds as there were three trittyes in each tribe. And a trittye was formed out of a collection of demes.

A deme was a small political and geographical area, think of it as a neighbourhood, a parish or a district. There were around 139 of them, give or take a few, in Attica. Demes were the new identifier, you registered the birth of a boy in your deme. A deme had its own elected representative, a demarchos and a deme, not your father’s name, became how you referred to yourself. You were no longer Neil, son of Berni. You were Neil of the deme of Tarring.

But demes differed in size and composition. A deme in the agricultural farmlands of Attica might be very different from one on the coast. For example, the coastal deme may have more lower class workers, whereas the agricultural deme might have a rich landowner or two. The problem was ensuring that each tribe was a mix of demes from all over Attica rather than one tribe being all coastal demes for example.

The solution was simple and brilliant. Cleisthenes carved Attica into three main areas, the coast, the City and the inland. Demes from each area were grouped into trittyes, or thirds and then these were combined to form a tribe. Each of the new ten tribes had a trittye of demes from the coast, a trittye of demes from the inland and a trittye of demes from the city.

As well as balancing out each tribe this broke down the traditional power bases which clans had used in the past. There had been instances of a faction building support from a particular region, that faction could then use this support for political means. But now the deme bordering on yours could be part of a different tribe. It immediately prevented this type of thing happening again. Factions could no longer rely on a geographical region for support as they had done in the past. Loyalty was now to your deme, your trittye, your tribe and above all Athens.

Each tribe elected a general, it also elected by lot I should add, 50 members to serve for a year on the new Council of 500. This was a body which drafted legislature and policy. This was then voted on by the Assembly which any citizen could attend. They literally sat on a hill called the Pnyx and voted with a show of hands. It’s thought it could accommodate up to 6,000 people which makes its name, which meant ‘squeeze together’, quite appropriate.

6,000 might not sound a lot, well, perhaps not until you consider the population of Attica at this time. It’s notoriously difficult get anything close to an exact figure but estimates for the entire population of Attica hover around the 250,000 mark. Hold on you might say, 6,000 doesn’t match well here. But that 250,000 was everyone, it was men, women, children and slaves and not everyone could vote. The number of adult citizen males is estimated at 30,000. These after all were the participants in the new system, so it doesn’t sound like a bad ratio. And remember that most would have lived outside of Athens, perhaps only coming in to vote on occasion.

Other reforms included the reorganisation of the law courts where jurors were paid and this was very popular. However, not all concessions to the masses had been granted. This was a balancing act after all. The poorest class, the thetes, didn’t have access to political office. There was also the Areopagus, a court which was still the reserve of the nobles and the classification by wealth was still a thing. And the classification by wealth thing, those 4 classes, that was still in place.

I should note that for some scholars what Cleisthenes had put in place still felt short of what was a real democracy and there were changes in the mid 5th century BC which favoured the poor even further. However, what Cleisthenes had done was build upon elements established by Solon, there was also now much more participation and the new tribes led to a new way of operating.

So we’ve arrived at the famous reforms of Cleisthenes but before I finish I want to pick up on three points, two of which I mentioned earlier the embassy to Persia and the assassination. I’ll start with the one I didn’t mention and one which has been commented as syncronising with democracy and that was was the development of Greek theatre.

Exactly when this came in is debated and there’s my episode on Greek theatre which covers this. Greek theatre has been argued as dovetailing with democracy, the two unlikely bedfellows. Before theatre made its way to Athens it was being perfomed in the demes outside of the city. And it was being performed in the spaces where debates were now being had. Usually this was at the foot of a hill on a flat piece of ground. Not the grandiose stone theatres you now see, but wil people sitting on the ground or at most some wooden benches.

Greek theatre early on was Greek tragedy and Greek tragedy, as Professor Edith Hall noted, was about decisions. Much of Greek tragedy is characters debating a point. Professor Hall made an excellent suggestion that Greek tragedy could have been a training exercise as much as an art. The people watching in a rural deme were learning about how consequential decisions might be and they would be flexing these newly built muscles in the Assembly or Council. Or perhaps just in their deme as they debated on who to elect as demarchos.

The second point is that embassy to Persia. If it raised an eyebrow then good. By agreeing to the symbolic gift of earth and water Athens had essenatially given its authority over to Persia. And when a certain Hippias starting pleading his case to Persia that he should be returned they agreed. Athen’s refusal to this was part of what caused Persia to invade in 490 BC. In fact Hippias was at Marathon but died shortly after. The Athenians used Marathon as a real win for democracy, in fact you can listen all about this on an episode I recorded with Dr Sonya Nevin. The fact that democracy helped cause the battle of Marathon in the first place is something of an irony.

The third and last point relates to how Athens set about creating a myth about the founding of democracy. It centred on the assassination of Hipparchus, the brother of Hippias at the Panathenaic games in 514 BC.

Two individuals were credited and celebrated for this, step forward Harmodius and Aristogeiton. Neither survived the event with Harmodius killed on the spot and Aristogeiton shortly afterwards. For later Athens these men, in fact they were lovers, embodied the noble action of killing a tyrant which paved the way for democracy and paying the ultimate price for it. The pair had a statue celebrating them in the Agora and even a hero cult. Their act became a byword for a Athens and its new political structure. Even today there’s a famous statue of the pair called the tyrannicides.

But upon closer examination this story sort of falls apart. Leading the charge on this was Thucydides who criticised his fellow Athenians for believing it. His version and that of Herodotus gave a different account. True the pair had killed Hipparchus, but he wasn’t the tyrant, he was the tyrant’s brother. The justification for the act wasn’t an altruistic sense of freeing the people. This was a revenge killing amongst nobles as Hipparchus had shamed the sister of Harmodius. There’s irony here as well because it was following this event that Hippias, the actual tyrant, started acting in the way we think of in the modern day. If anything Harmodius and Aristogeiton had created a tyrant in the modern sense. For those of you with an ear for detail this occurred in 514 BC, several years before the reforms of Cleisthenes.

There’s also one other thing the myth does. It completely removed the involvement of the Spartans. You know, the ones who actually drove Hippias from Athens. The reworking of this event into a sort of foundation myth for democracy had a number of benefits to it then. It was a great story showcasing just how dedicated Athenians were to be free and avoided giving any credit to Sparta which, in the 5th century, can only have been a good thing for them.

And on that point I come to the end of the episode. I hope you’ve enjoyed it. If you’ve been waiting for a new episode for a while, apologies for the delay. Real life stuff has a habit of getting in the way, I’m sure you know what I mean.

If you can leave a review or rating that would be great but more importantly thanks for listening. Until next time, keep well and stay safe.