Around 511 AD a man called John arrived at Constantinople seeking employment in the Imperial Palace. John had travelled from Philadelphia, in modern day Turkey and already had some experience as a clerk. Upon securing a minor bureaucratic position in the Imperial Palace he worked his way up, by the time of his death (circa 560) he had worked in the higher echelons of the Palace. Yet he had also made a name for himself outside his daily duties.

John was a scholar of no mean ability, particularly in Latin. His three works reveal a character who was capable of both niche topics and the grander type. The history of Roman bureaucracy reflected his own clerical insights, whereas the work on the Roman calendar and holidays was an ambitious venture. However, the one which we owe him thanks was titled De Ostentis (On Omens).

When composing De Ostentis John had referred to an earlier source, the largely unknown Publius Nigidius Figulus. Active in the 1st century BC Figulus was celebrated by Cicero as a man who knew much about divination and its history. Having served as a Praetor in 58 BC Figulus saw any political career cut short when he sided with Pompey against Julius Caesar. Exile followed after Pompey’s defeat.

Contained within the writings of Figulus was a record of a calendar which was used by the Etruscans to interpret the will of the gods. They did so not through a regular sacrifice or reading of entrails. The Etruscans also used thunder, otherwise known as brontoscopy. What nestled in the writings of Figulus and which survived through John’s later inclusion of it was a calendar which explained what thunder might mean if heard on any day of the year. It is known as the Etruscan brontoscopic calendar.

Etruscans and brontoscopy.

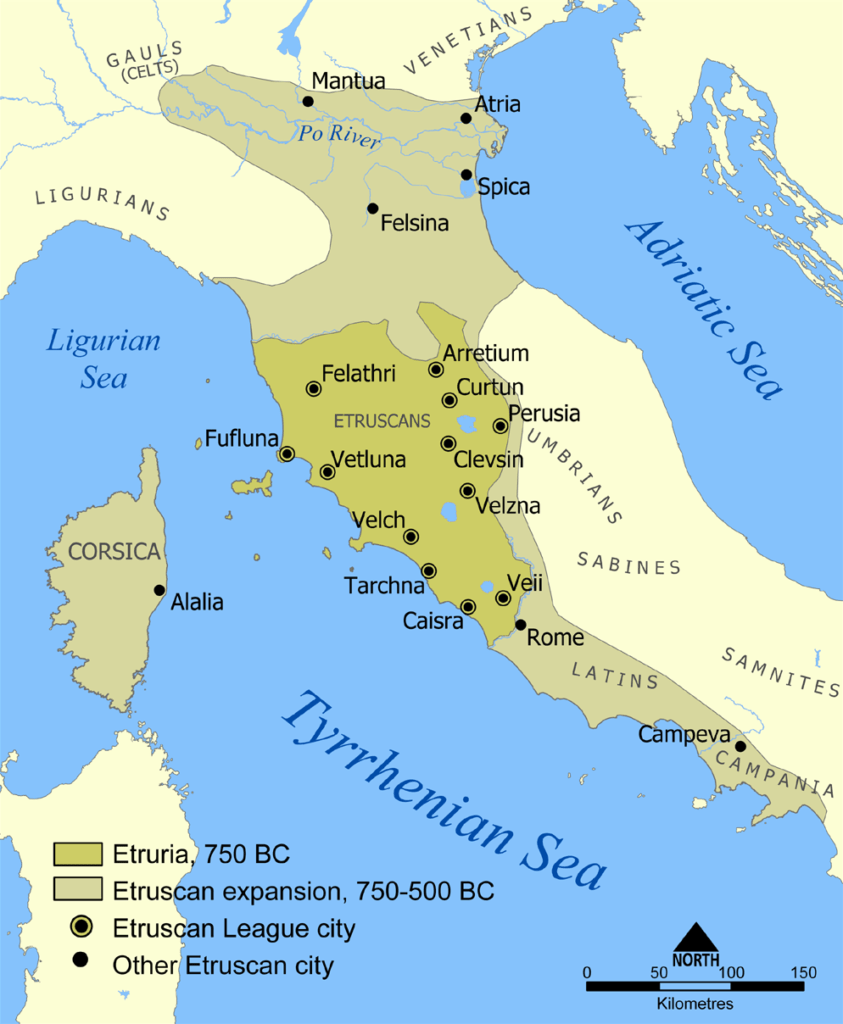

The Etruscans, a people who were profoundly important by themselves but also through their influence on the nascent Rome, were well versed in divination. Though the myth of early Rome including its kings is mythical at best there was a firm understanding that Etruscans had midwifed the early Roman city culturally. From the technology to manage the flooding Tiber (and the building of the Cloaca Maxima) through to togas and curile chairs.

Brontoscopy became a feature at Rome through the mythical second king, Numa. He was said to have established the altar to Jupiter Elicius, the rites performed here could invoke a storm. The resulting thunder would then give a clue as to the will of the gods. There is a sense that this wasn’t the safest of rituals as Numa wore a charm which protected him from lightning. One account of the death of Tullius Hostilius, the king who followed Numa, was that he had performed rites at the altar incorrectly and was killed by lightning. Brontoscopy, it seems, came with a catch.

The regal period at Rome (753-509 BC) sat in the mythical past, and the calendar Figulus recorded is argued to have dated to around this time. The calendar wasn’t a recent invention by Figulus. Dates for it range between the 9th and 7th century BC and Tarquinia is pointed to as the location of its composition.

Unlike our modern calendar the Etruscan Brontoscopic Calendar starts in June and doesn’t seem to consider thunder a particularly welcome omen. No more than 10 incidents of thunder predict pleasant outcomes, the majority predict crop failings or some form of pestilence. For an agrarian culture the prominence with which agriculture features makes sense (as Turfa points out). But other dangers waited in the heavens, these ranged from civil disorder to leaders acting as tyrants. Rome might suffer a failure in its political system as much as in the field.

Notable dates.

In case you are curious, here are some dates and what they would predict if thunder was heard.

February 14th.

Loss of progeny and onslaught of poisonous reptiles.

April 1st

Civil discord and downfall of fortunes.

July 4th.

The airs will be turbulent.

December 25th.

A movement of troops to war, but this will be favourable.

If you aren interested in some more dates – here’s a piece about eclipses in antiquity and how they have been used to date some famous events.

Bibliography.

The Etruscan Brontoscopic Calendar and Modern Archaeological Discoveries, Jean MacIntosh Turfa

John Lydus. On the Months, trans with introduction by Mischa Hooker

The Religion of the Etruscans, ed Thomson and de Grummond.